Review of the distribution and biology of the snake mite Ophionyssus natricis (Acari: Macronyssidae)

Orlova, Maria V.  1

; Halliday, Bruce

1

; Halliday, Bruce  2

; Reeves, Will K.

2

; Reeves, Will K.  3

; Doronin, Igor V.

3

; Doronin, Igor V.  4

; Mishchenko, Vladimir A.

4

; Mishchenko, Vladimir A.  5

; Vyalykh, Ivan V.

5

; Vyalykh, Ivan V.  6

and Kidov, Artem A.

6

and Kidov, Artem A.  7

7

1✉ Tyumen State Medical University, Tyumen, Russia & National Research Tomsk State University, Tomsk, Russia & Federal Scientific Research Institute of Viral Infections «Virome» of Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, Ekaterinburg, Russia.

2Australian National Insect Collection, CSIRO, Canberra, Australia.

3C. P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Fort Collins, USA.

4Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Science, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

5Federal Scientific Research Institute of Viral Infections Virome of Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, Ekaterinburg, Russia.

6Federal Scientific Research Institute of Viral Infections Virome of Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, Ekaterinburg, Russia.

7Russian State Agrarian University – Moscow Agricultural Academy named after. K. A. Timiryazev, Moscow, Russia.

2024 - Volume: 64 Issue: 2 pages: 637-653

https://doi.org/10.24349/gmr0-8m9oOriginal research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

Mites in the family Macronyssidae (Acari: Mesostigmata: Gamasina) are mostly obligate blood-sucking ectoparasites of mammals, birds and reptiles. The family currently includes 34 genera with approximately 240 species (Radovsky, 2010). The genus Ophionyssus Mégnin, 1884a currently includes 14 species worldwide (Beron, 2014). The most extensively studied species in the genus is the snake mite Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais, 1844), which naturally infests snakes and lizards in Africa (Till, 1957; Evans & Till, 1966), but in other parts of the world it is associated primarily with animals in captivity (Miranda et al., 2017; Norval et al., 2020). Our purpose in this paper is to review the published data on the geographic distribution and host range of the snake mite, and to summarise the available information about its clinical significance.

Material and methods

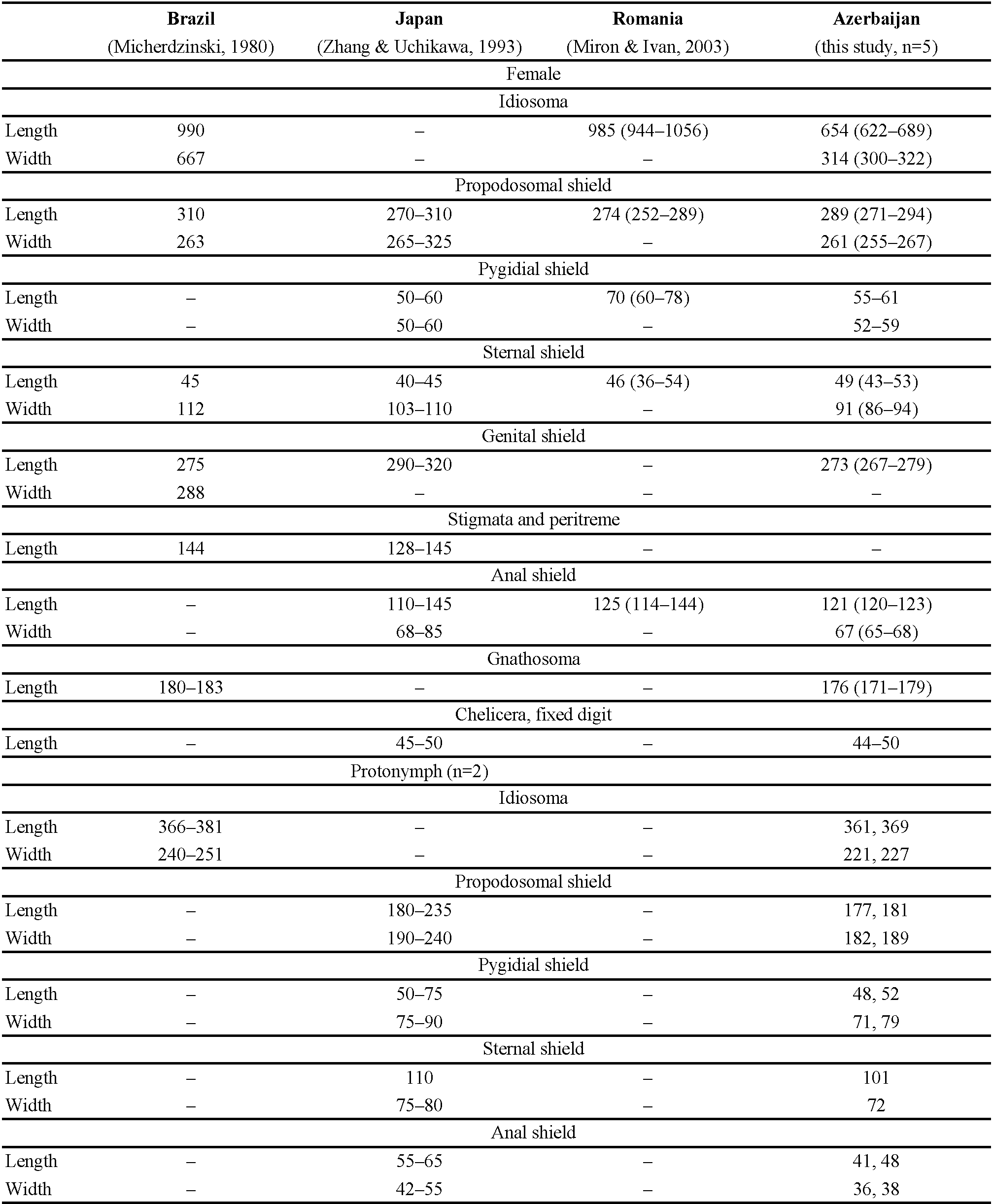

Most of the information presented here was derived from a search of the literature using Web of Science ® and Google Scholar ®, and from the personal libraries of the authors. We collected new information by examining specimens in the Reptile Collection of the Zoological Museum of the Moscow State University (ZMMU) and in the terrarium of the Russian State Agrarian University – Moscow Agricultural Academy. Mites were collected from the body surface of lizards by forceps, transferred to 70% alcohol, and mounted on microscope slides in Faure-Berlese medium. Mites were identified based on keys and descriptions given by Bregetova (1956) and Moraza et al. (2009). Measurements of body parts of imaginal and pre-imaginal stages are presented in Table 1. External measurements were taken in micrometres (μm). Slide-mounted voucher specimens were deposited in the collection of the Parasitological Collection of the Tyumen State Medical University (Tyumen, Russia). The classification of reptiles is based on Uetz et al. (2023).

New material examined

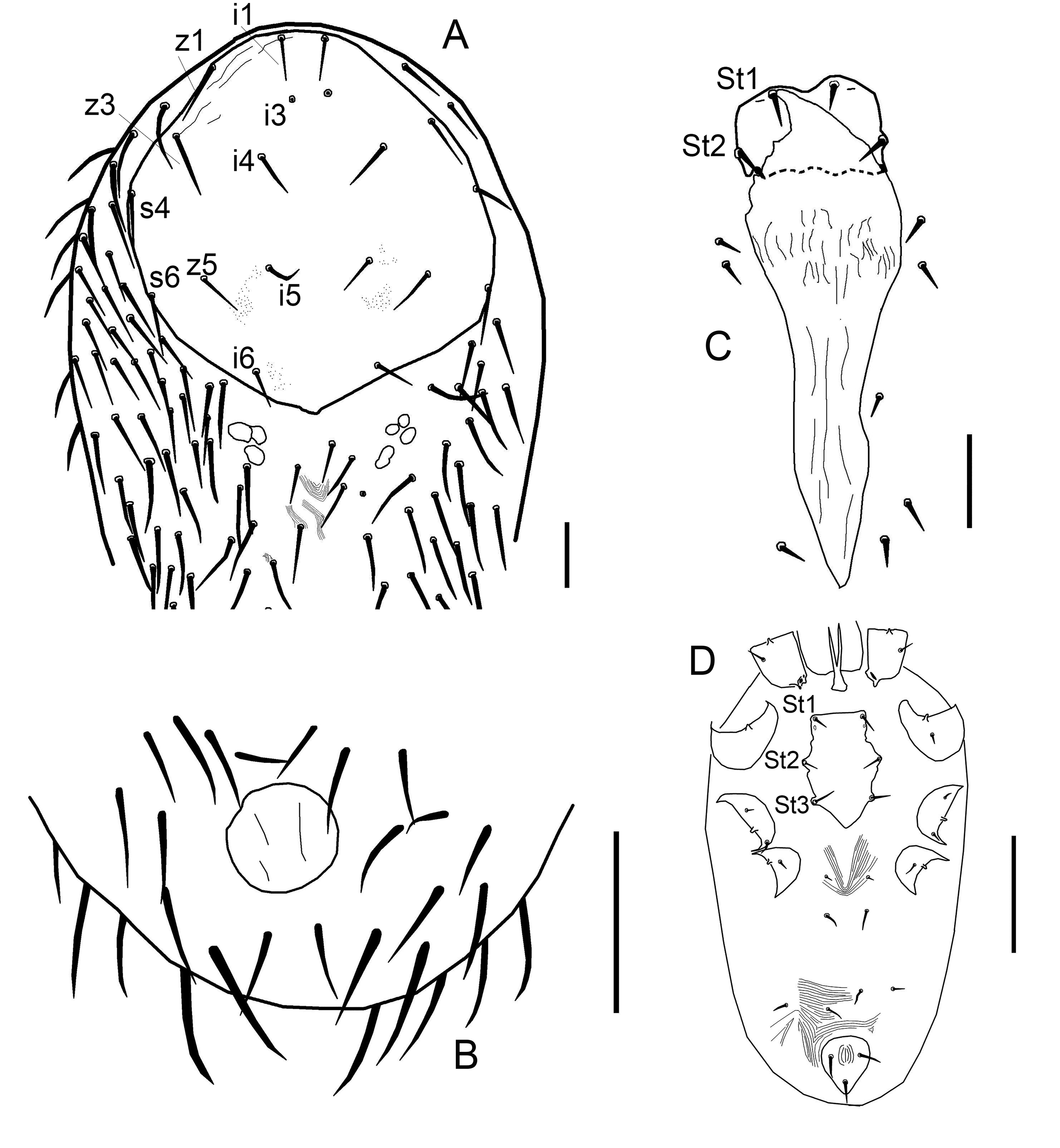

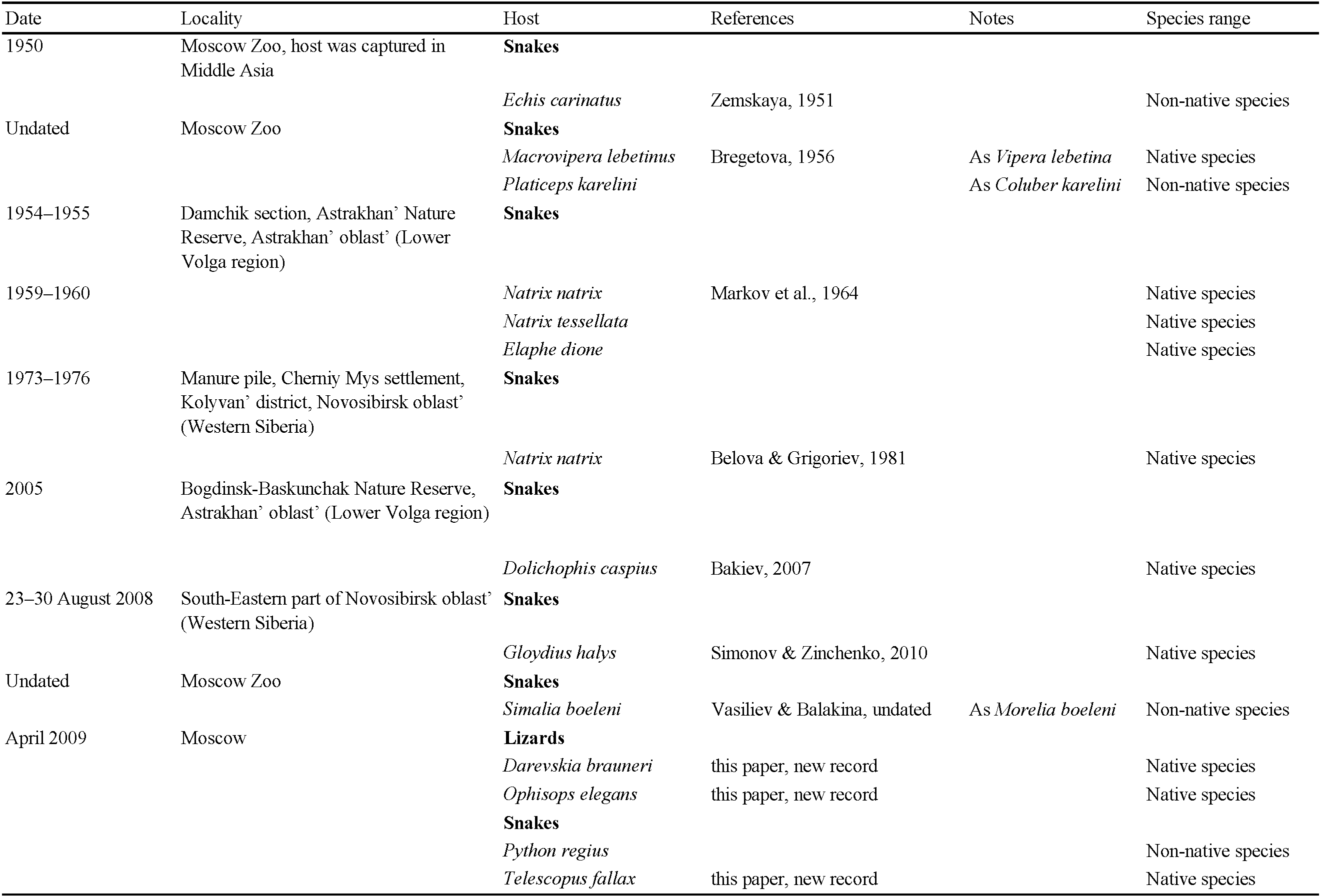

Five females, two protonymphs from Ophisops elegans Ménétries, 1832 from Azerbaijan, Lerik District, Zuvand settlement vicinity 38°47′ N, 48°25′ E, April 2009, leg. A.A. Kidov, identified by M.V. Orlova (Figure 1, Table 2). Additional specimens from Darevskia brauneri (Méhely, 1909) from Russia, Krasnodar region, Ubinskaya settlement, 44°42′N, 38°31′ E, leg. and det. A.A. Kidov; and from Python regius (Shaw, 1802) and Telescopus fallax Fleischmann, 1831, April 2009, from terrarium of Russian State Agrarian University (Moscow), identified by A.A. Kidov. It is most likely that the snakes and lizards acquired O. natricis during their stay in the terrarium in Moscow, so we attributed this record to Russia, not to Azerbaijan (Table 3). Our records of O. natricis for Ophisops elegans, Darevskia brauneri and Telescopus fallax are new host records.

Results

Taxonomic background

The first published reference to the snake mite appears to be that of Metaxa (1823), who observed undentified mites on captive snakes in Italy. Dugès (1834) found it in France and noted its similarity to the bird mite Dermanyssus avium Dugès, 1834. It was first named as Dermanyssus natricis by Gervais (1844), based on specimens collected on captive reptiles in Paris. The same species was also described by several other authors under different names. Camin (1949), Till (1957), Fain (1962) and Micherdzinski (1980) reviewed the earlier literature on the species and listed these junior synonyms, and that information need not be repeated here.

Ophionyssus natricis has been throughly described and illustrated several times, notably by Camin (1953) and Micherdzinski (1980). Moraza et al. (2009) provided detailed information on how O. natricis can be distinguished from other species of Ophionyssus. The morphological recognition of the species is supported by molecular sequence data (Alfonso-Toledo & Paredes-León, 2021). We now provide a list of some of the major taxonomic references to the species, including the important recent works by Moraza et al. (2009), Radovsky (2010) and Beron (2014).

Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais, 1844)

Dermanyssus natricis Gervais, 1844: 223.

Ophionyssus natricis Mégnin, 1884a: 617; 1884b: 110; André, 1937: 62; Vitzthum, 1943; 771; Fonseca, 1948: 313; Camin, 1949: 583; 1953; 3; Zemskaya, 1951: 49; Baker et al., 1956: 33; Bregetova, 1956: 223; Keegan, 1956: 219; Womersley, 1956: 599; Till, 1957: 126; Schweizer, 1961: 155; Fain, 1962: 107; Domrow, 1963: 214; 1974: 17; 1985: 152; 1988: 857; Evans & Till, 1966: 337; Beron, 1966: 52; Costa, 1966: 75; Hallas, 1978: 28; Mehl, 1979: 33; Arutunjan & Ohandjanian, 1983: 312; Zhang & Uchikawa, 1993: 76; Moraza et al., 2009: 65; Radovsky, 2010: 108; Beron, 2014: 130.

At least five other species names are now considered to be junior synonyms of O. natricis (see Beron, 2014 for details).

Misidentifications of Ophionyssus natricis

Some published records of O. natricis actually refer to other species. Biological Services (2015) includes an illustration of a mite on the head of a snake, but the mite appears to be Ophiomegistus Banks, 1914 and not Ophionyssus. The illustration of a snake mite in Maxwell (2022) shows an oribatid mite. Sabu et al. (2002) reported a mite they identified as O. natricis on snakes in India. Their illustration shows an unidentified species of Astigmata, not O. natricis, and the occurrence of O. natricis inside nodules of necrotic tissue as they reported would be extremely unusual.

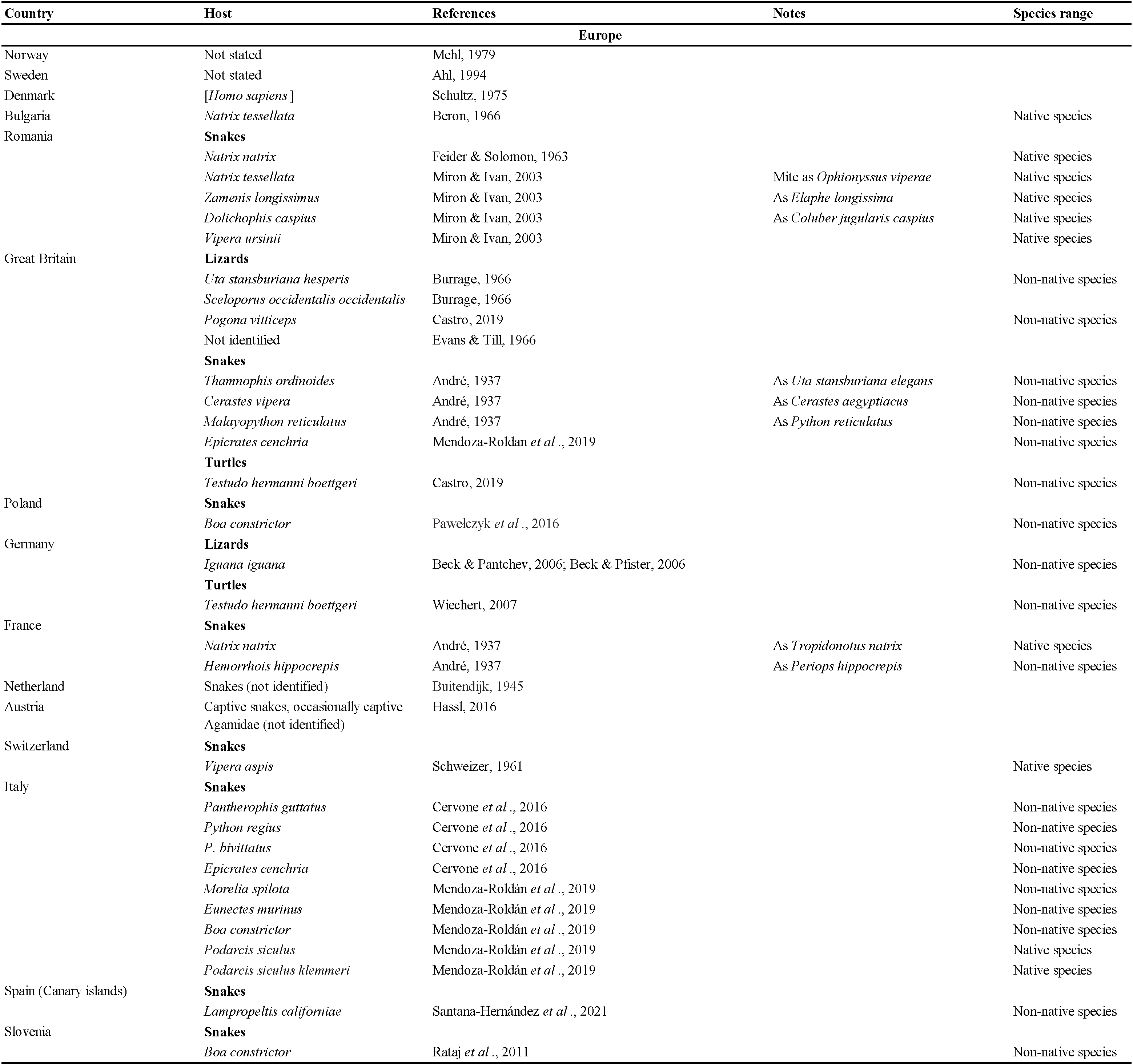

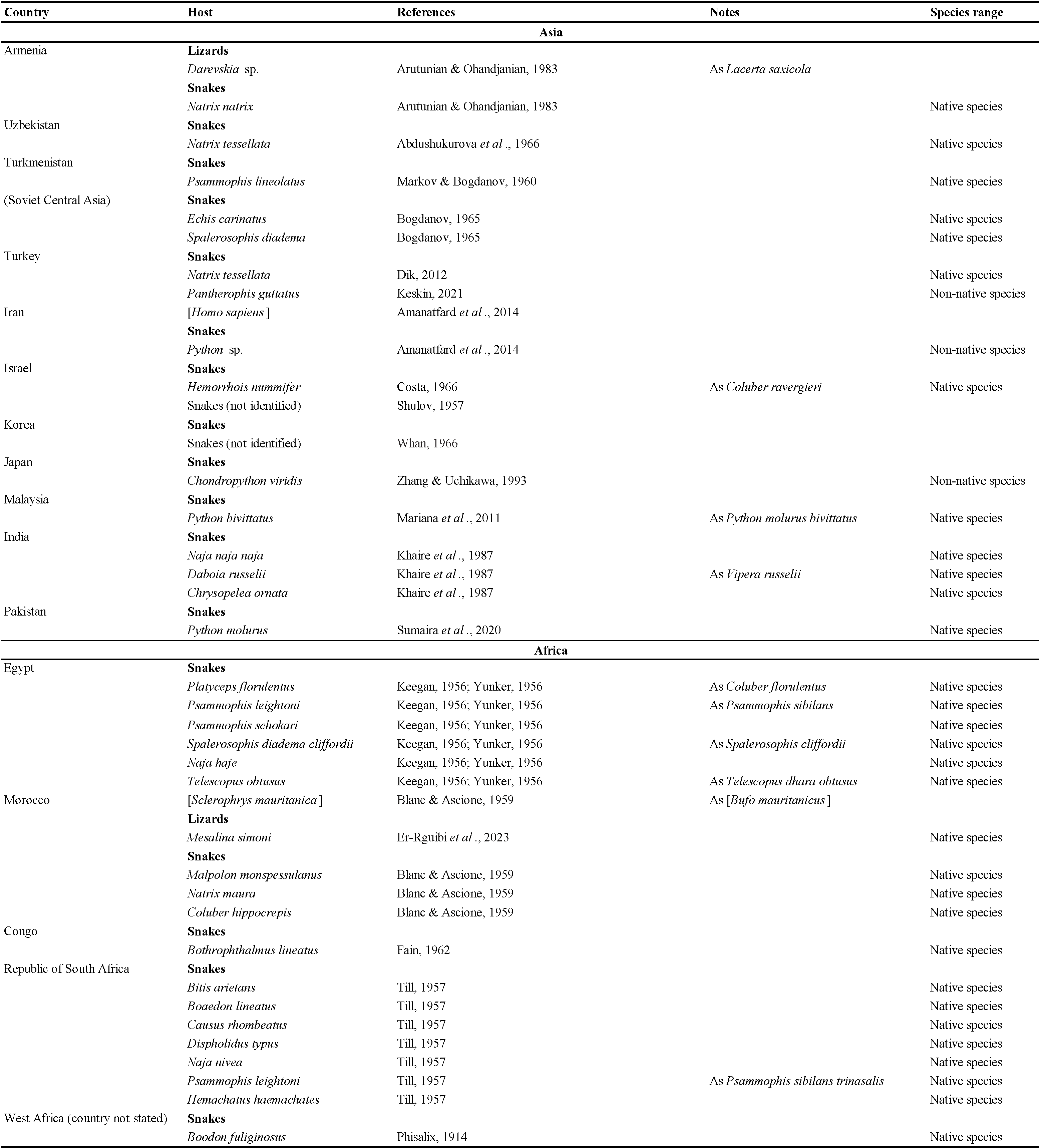

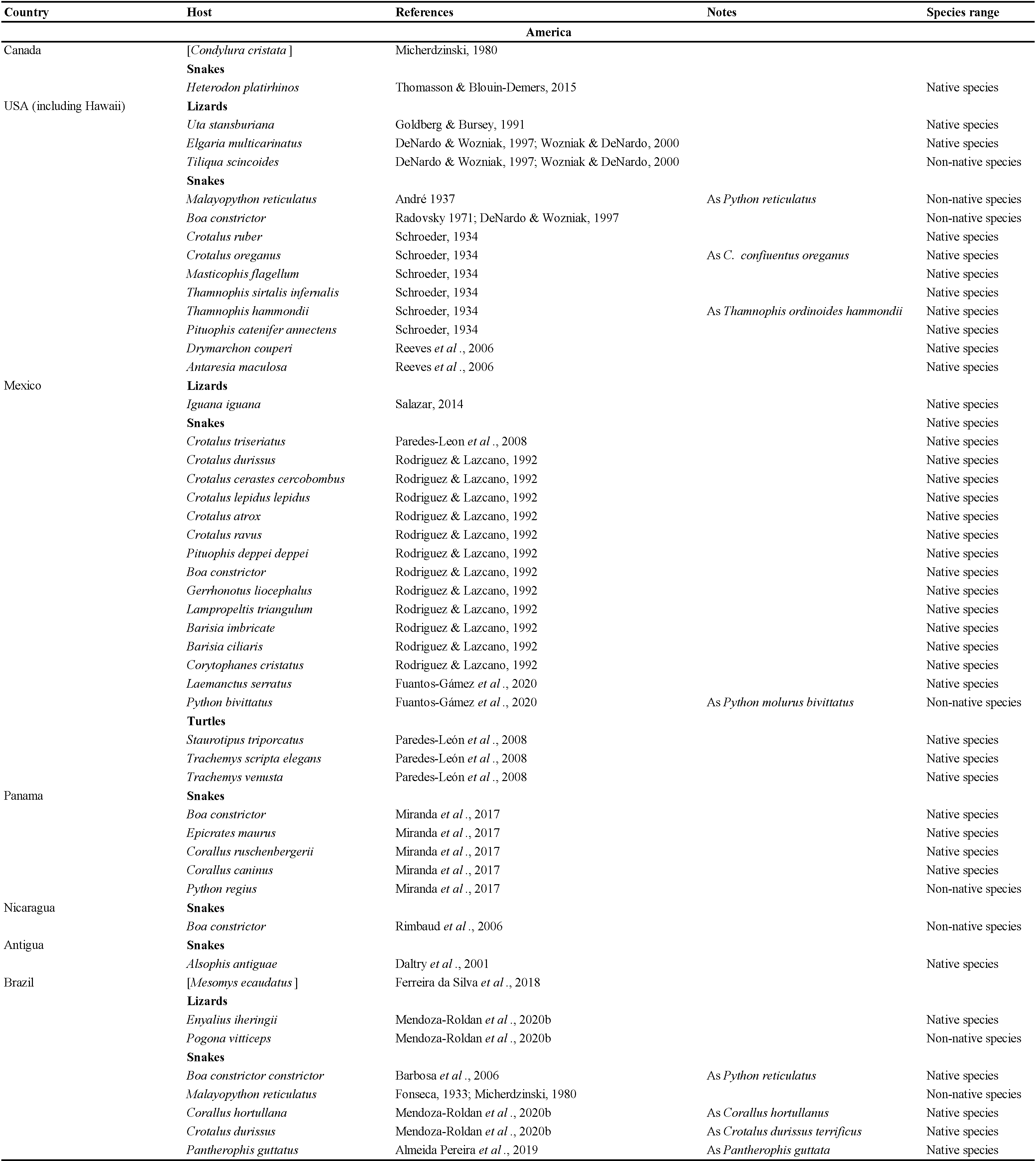

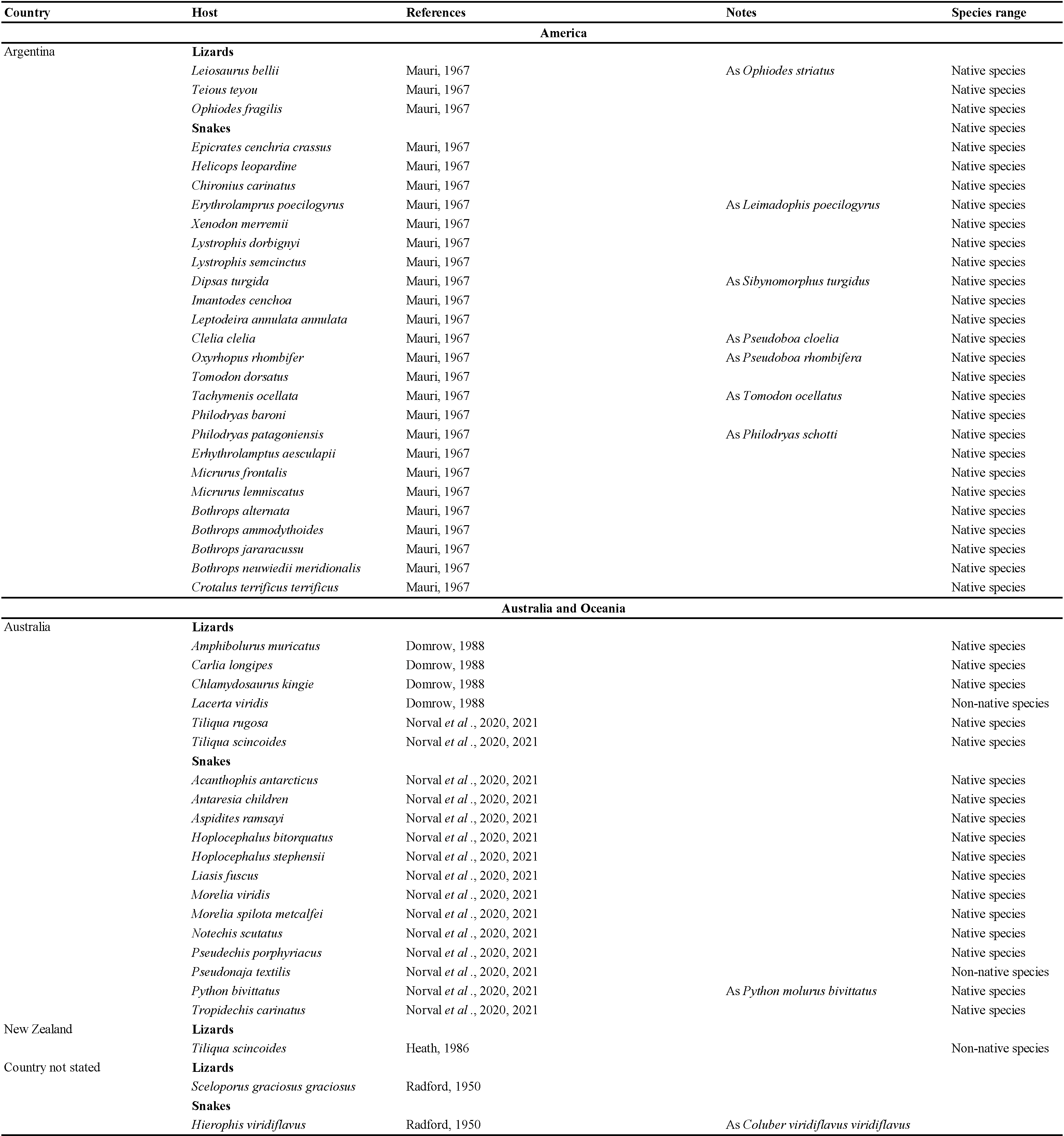

Geographic distribution

The data listed in Table 2 show that Ophionyssus natricis is near cosmopolitan, and has been found in every continent except Antarctica. Records for Russia are listed in more detail in Table 3. The apparent absence of O. natricis in China is surprising. Su et al. (2010) and Ma & Bai (2012) reported other species of Ophionyssus in China, and O. natricis will almost certainly be found there when further studies are carried out.

Life cycle and behaviour

The life cycle and behaviour of Ophionyssus natricis were examined in detail by Camin (1953). Individuals pass through the egg, larva, protonymph, and deutonymph stages before developing into adult males and females. Protonymphs and adults are hematophagous, feeding on the host and then molting in the environment, but larvae and deutonymphs do not feed. The life cycle can be completed within 7 to 14 days when environmental and host conditions are optimal, in temperatures ranging from 20º C to 30º C and humidity higher than 75%. Oliver (1971) summarised previous results showing that O. natricis reproduces by arrhentokous parthenogenesis, with nine chromosomes in males and 18 in females. Aspects of the biology and behaviour of O. natricis are described in a large number of publications, including the useful summaries by Reinert & Brandstätter (1993), Wozniak & DeNardo (2000), Fitzgerald & Vera (2006) and Schilliger et al. (2013).

Bannert et al. (2000) provided a detailed description of the life cycle of Ophionyssus galloticolus Fain & Bannert, 2000, which appears to be very similar to that of O. natricis.

Occurrence on aquatic hosts

Captive snakes infested by O. natricis seek relief from irritation by immersing themselves in water (for example Page, 1966; Šlapeta et al., 2018), and dead mites can be found floating in water bowls in terraria, suggesting that mites are easily killed by immersion in water. It therefore seems unlikely that reptiles that spend significant time in water would be acceptable hosts for this parasite. We conducted a Web of Science® search for records of O. natricis on marine and aquatic snakes in the following genera: Acrochordus Hornstedt, 1787; Afronatrix Rossman & Eberle, 1977; Agkistrodon Palisot de Beauvois, 1799; Aipysurus Lacépède, 1804; Cerberus Cuvier, 1829; Emydocephalus Krefft, 1869; Enhydris Sonnini & Latreille, 1802; Ephalophis Smith, 1931; Farancia Gray, 1842; Fowlea Theobald, 1868; Grayia Günther, 1858; Helicops Wagler, 1828; Homalopsis Kuhl & Hasselt, 1822; Hydrelaps Boulenger, 1896; Hydrophis Latreille, 1801; Hydrops Wagler, 1830; Laticauda Laurenti, 1768; Leptodeira Fitzinger, 1843; Myron Gray, 1849; Myrrophis Kumar et al., 2012; Natrix Laurenti, 1768; Nerodia Baird & Girard, 1853; Opisthotropis Günther, 1872; Parahydrophis Burger & Natsuno, 1974; Pseudoeryx Fitzinger, 1826; Ptychophis Gomes, 1915; Tretanorhinus Duméril et al., 1854; Trimerodytes Cope, 1895. Positive results were returned for Helicops, Leptideira, and Natrix. Mauri (1967) reported O. natricis on Helicops leopardinus (Schlegel, 1837) and Leptodeira annulata (Linnaeus, 1758) in Argentina. Both these species have been referred to as water snakes, but they are not completely aquatic (Ávila et al., 2006; Thaler et al., 2022). Feider & Solomon (1963), Markov et al. (1964), Bogdanov (1965), and Beron (1966) reported the snake mite on Natrix tessellata Laurenti, 1768 in Uzbekistan, Bulgaria, Romania and Russia (Astrakhan') but did not provide detailed collecting data. Chiodini et al. (1983) and Dik (2012) reported O. natricis on Natrix spp. in captivity but these hosts also cannot be considered as fully aquatic.

Some documents report the occurrence of O. natricis on crocodiles, but these all appear to be the result of mistakes or misunderstandings. Dhooria (2016) reported this host association without any reference to its source. It is also found on many internet sites including Biological Services (2015), Maxwell (2022), and Reptiles Cove (2022), but these records are not supported by evidence.

Wozniak & DeNardo (2000) referred to the host range of O. natricis as follows ''The mite has been shown to thrive on most snakes and some lizards including southern alligator lizards, Elgaira mulicarnata (Wozniak, personal observations), blue-tongue skinks Tiliqua scincoides (Wozniak, personal observations) and side-blotched lizards Uta stansburiana (Goldberg and Bursey, 1991)''. Mendoza-Roldan (2019) misquoted that information when describing O. natricis as ''a cosmopolitan inhabitant of captive snakes, but also infest captive lizards, turtles, crocodiles and other reptiles (Wozniak & DeNardo, 2000)''. This incorrect information was not repeated in Mendoza-Roldan et al. (2020a, 2020b), who reported O. natricis only on snakes and lizards.

Numerous publications refer to ectoparasites of crocodilians, including ticks and leeches, but none of these mention Ophionyssus sp. on this host (e.g. Jacobson, 1984; Magnusson, 1985; Huchzermeyer, 2003; Leslie et al., 2011; Tellez, 2013; Divers & Stahl, 2019; Partyka, 2019; Pereira & Colli, 2023). We have been unable to find any confirmed records of Ophionyssus sp. on any species of crocodilian.

Pest control

Snake mites are highly mobile, and can quickly infest and re-infest terraria or enclosures. They can survive for extended periods without feeding (Wozniak & DeNardo, 2000), so routine environmental hygiene alone is not an effective method of control. Fitzgerald & Vera (2006) reviewed the chemical pesticides used for control of snake mites, as well as a variety of cultural methods for limiting their populations. Commonly used insecticides and acaricides, including those previously reviewed by Camin et al. (1964), are potentially harmful to reptiles, and are not recommended for control of snake mites. Alternative methods of mite control have included the use of sorptive dust, which operates by causing dehydration (Tarshis, 1960). Fitzgerald (2019) listed the currently available methods for controlling snake mites, and the methods and materials that are no longer recommended. A new generation of isoxazoline compounds appears to have considerable potential to provide safe and effective mite control when administered to snakes orally without side effects and without the need to treat the environment of the snake (Fuantos-Gámez et al., 2020; Gobble, 2022; Mendoza-Roldan et al., 2023).

Some authors have proposed the use of predatory mites to control O. natricis on captive reptiles. Rotter (1963) used Cheyletus eruditus Schrank, 1781 (Acari: Cheyletidae) to control the snake mite on captive lizards, and C. eruditus is now available commercially for that purpose (Schilliger et al., 2013; APPI Biological Control, 2021). Stratiolaelaps scimitus (Womersley, 1956) (Acari: Laelapidae) may also have some effect as a predator in terraria, but its value is limited by its low tempertature optimum (Mendyk, 2015). Maslova & Dochevoy (2016) reported a carabid beetle (Carabus granulatus telluris Bates, 1883) moving around on the scales of a pitviper (Gloydius ussuriensis (Emelianov, 1929)) and feeding on ectoparasites, apparently including O. natricis.

Clinical significance

Infestation of reptiles with Ophionyssus natricis can cause dehydration, lethargy, growth impairment (Wozniak & DeNardo, 2000) and in severe infestations, anaemia and dysecdysis (DeNardo & Wozniak, 1997; Mendoza-Roldan et al., 2023). Affected individuals suffer hyperaemic and oedematous skin, and seek relief from the resulting pruritus by soaking in water (Wozniak & DeNardo, 2000). There have been reports of loreal pit inflammations and impactions associated with heavy infestations (Garrett & Harwell, 1991). Histopathologic evaluation of feeding sites shows infiltration with neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells, with multifocal perivascular aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the adjacent dermis (DeNardo & Wozniak, 1997).

Ophionyssus natricis is a mechanical vector of Aeromonas hydrophila Chester, 1901, the causative agent of hemorrhagic disease in reptiles (Mendoza-Roldan et al., 2021). It can be a vector of blood-borne protozoa and viral pathogens of snakes (Camin, 1948; Chiodini et al, 1983; Schumacher et al, 1994; Mendoza-Roldan et al., 2023). In South America it was identified as a vector of Hepatozoon sp. and Rickettsia sp. (Mendoza-Roldan et al., 2020a, b). It has also been implicated as vector of Arenavirus sp., the etiological agent of the Inclusion Body Disease in boid snakes (Chang & Jacobson, 2010; Divers & Stahl, 2019). Ophionyssus natricis collected from Boa constrictor in Italy also contained Wolbachia sp. (Manoj et al., 2021). Further vector competency studies are needed to characterise the overall role of this parasite in the transmission of other infectious agents, such as filariids.

This parasite can become a pest to humans due to the aggressive feeding of the protonymphs, which swarm and bite humans, causing papular vesiculo-bullous eruptions in the skin (Schultz, 1975; McClain et al., 2009), other bite-associated dermatitis (Beck, 1996; Amanatfard et al., 2014), and the risk of zoonotic transmission of pathogens.

Ecological significance

Schroeder (1934) presented a very clear description of the life cycle of O. natricis, and its importance as a pest of snakes in captivity. He also pointed out the agricultural value of snakes as a natural means of reducing rodent populations. Fonseca (1948), citing Schroeder (1934), speculated that O. natricis was harmful to wild snake populations, and therefore indirectly influenced wild rodent populations. That conclusion is not supported by the observation that O. natricis rarely reaches heavy levels of infestation of snakes in natural habitats.

Discussion

The catalogue of the family Macronyssidae by Beron (2014) provides a good taxonomic background to the systematics of Ophionyssus natricis. The genus Ophionyssus currently includes 14 valid species. Several other species have been placed in Ophionyssus at some time, but have since been transferred to other genera, including Thigmonyssus myrmecophagus (Fonseca, 1954), Trichonyssus ehmanni (Domrow, 1985), T. galeotes (Domrow et al., 1980), and T. scincorum (Domrow et al., 1980).

Most species of Ophionyssus have a limited geographic distribution but O. saurarum (Oudemans, 1901) is widespread in Europe, Asia, and Africa, and O. natricis is cosmopolitan. If we exclude O. natricis, the highest level of species diversity in the genus is found in Africa, with five species in southern Africa and a further three in the Canary Islands. Two species have been described from the Indo-Australian Region, and four occur in Europe and the Western Palaearctic.

Ophionyssus natricis occurs on a very wide range of snake and reptile hosts, while other species of Ophionyssus parasitise lizards in the families Lacertidae, Scincidae, Cordylidae, Agamidae, and Pygopodidae. Reptilian hosts of O. natricis include three families of turtles, 10 families of lizards, and seven families of snakes. The snake family with the largest number of infested species (46) is Colubridae, reflecting the fact that it is the most numerous group of modern snakes, with more than half of all known species. Approximately 20% of the hosts are terrarium species that are not typical of the countries where the infested specimens were found.

The evolutionary history of O. natricis has been obscured by human-assisted dispersal. Till (1957) recorded its presence on both snakes and lizards in wild conditions in South Africa. Field records of O. natricis in other countries are rare, suggesting that the species may have arisen in southern Africa, possibly following a host shift from a lizard to a snake. Nieri-Bastos et al. (2011) and Gomes-Almeida & Pepato (2021) demonstrated the potential value of molecular systematics in Macronyssidae. The required sequence data is not yet available for Ophionyssus, so a molecular analysis of the phylogenetic background of the snake mite is not yet possible.

Ophionyssus natricis has recently been found on wild populations of lizards in Australia (Norval et al., 2020, 2021). Research is needed to determine whether this parasite represents a serious threat to wild populations of reptiles, both in Australia and elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (topic no. 122031100282-2). Especial thank to Nikolay V. Anisimov (Tyumen State University, Russia) for his help with pictures. Authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- Abdushukurova R.U., Markov G.S., Bogdanov O.P. 1966. On the parasitic fauna of the dice snake. Vertebrates of Central Asia (Collection of articles dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR T.Z. Zahidov). Tashkent, Fan Publishing House. p. 215-220. [In Russian]

- Ahl I. 1994. Snake mites Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais 1844) more common than snakes in the terrarium? Litteratura Serpentium, 14: 9-24.

- Alfonso-Toledo J.A., Paredes-León R. 2021. Molecular and morphological identification of dermanyssoid mites (Parasitiformes: Mesostigmata: Dermanyssoidea) causatives of a parasitic outbreak on captive snakes. Journal of Medical Entomology, 58: 246-251. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjaa164

- Almeida Pereira J., de Araújo Barreto L., Vianna C.A.B., de Oliveira Henriques M., de Sousa Oliveira Batista Cirne L.C. 2019. Diagnóstico e tratamento de serpentes Pantherophis guttata (corn snake) infestadas com Ophionyssus natricis: relato de caso. Revista Agrária Acadêmica, 3: 202-206. https://doi.org/10.32406/v2n32019/202-206/agrariacad

- Amanatfard E., Youssefi M.R., Barimani A. 2014. Human dermatitis caused by Ophionyssus natricis, a snake mite. Iranian Journal of Parasitology, 9: 594-596.

- André M. 1937. Sur l′Ophionyssus natricis Gervais, acarien parasite des reptiles. Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, 9: 62-65.

- APPI Biological Control. 2021. TAURRUS Natural Enemies of reptile mites. https://www.taurrus.co.uk/. Version dated 2021, date of access 19 October 2023.

- Arutunjan E.S., Ohandjanian A.M. 1983. Parasitic gamasid mites from the Sevan Basin. Academy of Science of Armenian SSR, Institute of Zoology, Zoological Papers, 19: 300-318. [In Russian]

- Ávila R.W., Ferreira V.L., Arruda, J.A.O. 2006. Natural history of the South American water snake Helicops leopardinus (Colubridae: Hydropsini) in the Pantanal, Central Brazil. Journal of Herpetology, 40: 274-279. https://doi.org/10.1670/113-05N.1

- Baker E.W., Evans T.M., Gould D.J., Hull W.B., Keegan H.L. 1956. A Manual of Parasitic Mites of Medical or Economic Importance. National Pest Control Association, New York. pp. 170.

- Bakiev A.G. 2007. Overall results of snakes' parasites investigation in the Volga River Basin. Communicate 2: Parasitiformes. Bulletin of Mordovia University, Biological Sciences, 4: 68-70. [In Russian]

- Banks, N. 1914. New Acarina. Journal of Entomology and Zoology, 6: 55-66.

- Bannert, B., Karaca H.Y., Wohltmann A. 2000. Life cycle and parasitic interaction of the lizard-parasitizing mite Ophionyssus galloticolus (Acari: Gamasida: Macronyssidae), with remarks about the evolutionary consequences of parasitism in mites. Experimental and Applied Acarology, 24: 597-613. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026504627926

- Barbosa A.R., Silva H., Albuquerque H.N., Ribeiro I.A.M. 2006. Contribuição ao estudo parasitológico de jibóias, Boa constrictor constrictor Linnaeus, 1758, em cativeiro. Revista de Biologia e Ciências da Terra, 6: 1-19.

- Beck W. 1996. Tierische Milben als Epizoonoseerreger und ihre Bedeutung in der Dermatologie. Der Hautarzt, 47: 744-748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001050050501

- Beck W., Pantchev N. 2006. Schlangenmilbenbefall (Ophionyssus natricis) beim Grünen Leguan (Iguana iguana) - Ein Fallbericht. Kleintierpraxis, 51: 648-652.

- Beck W., Pfister N. 2006. Humanpathogene Milben als Zoonoseerreger. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 118, Supplement 3, 27-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-006-0678-y

- Belova O.S., Grigoriev O.V. 1981. Occurrence of gamasid and ixodid ticks of reptiles of Western Siberia. In: Borkin L.J. (ed.) Herpetological Investigations in Siberia and the Far East. Leningrad: Zoological Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences. p. 16-18.

- Beron P. 1966. Contribution à l′étude des acariens parasites des reptiles en Bulgarie. Bulletin de l′Institut dе Zооlоgiе et Musée, 22: 51-53. [in Bulgarian]

- Beron P. 2014. Acarorum Catalogus. III. Parasitiformes: Opilioacarida, Holothyrida, Mesostigmata. Sofia: Pensoft. pp. 286.

- Biological Services. 2015. Snake/reptile mite Ophionyssus natricis. Avaible from https://biologicalservices.com.au/pests/snake-reptile-mite-92.html. [13 Oct 2023].

- Blanc G., Ascione L. 1959. Sur la presence d'Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais 1844) sur trois serpents du Maroc des Forets de Nefifik et du Cherrat. Archives de l′Institut Pasteur du Maroc, 5: 666-668.

- Bogdanov O.P. 1965. Ecology of reptiles in Middle Asia. Tashkent, Science. p. 213. [in Russian]

- Bregetova N.G. 1956. Gamasid mites (Gamasoidea), a brief guide. Moscow: Zoological Institute, USSR Academy of Sciences. p. 247. [in Russian]

- Buitendijk A.M. 1945. Voorloopige catalogus van de Acari in die collectie-Oudemans. Zoologische Mededelingen, 24: 281-391.

- Burrage B.R. 1966. Observations on the macronyssid mite (order Acarina), Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais), on the two iguanid lizards, Uta stansburiana hesperis and Sceloporus occidentalis occidentalis. British Journal of Herpetology, 3: 275-278.

- Camin J.H. 1948. Mite trasmission of a hemorrhagic septicemia in snakes. Journal of Parasitology, 34: 345-354. https://doi.org/10.2307/3273698

- Camin J.H. 1949. An attempt to clarify the status of the species in the genus Ophionyssus Mégnin (Acarina: Macronyssidae). Journal of Parasitology, 35: 583-589. https://doi.org/10.2307/3273637

- Camin J.H. 1953. Observations on the life history and sensory behaviour of the snake mite, Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais) (Acarina: Macronyssidae). Special Publications, The Chicago Academy of Sciences, 10: 1-75 + Plates I-III.

- Camin J.H., Clarke G.K., Goodson, L.H., Shuyler, H.R. 1964. Control of the snake mite, Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais), in captive reptile collections. Zoologica: Scientific Contributions of the New York Zoological Society, 49: 65-79. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.203293

- Castro P.D.J. 2019. Ectoparasites in captive reptiles. Avaible from https://www.theveterinarynurse.com/review/article/ectoparasites-in-captive-reptiles [26 June 2023] https://doi.org/10.12968/vetn.2019.10.1.33

- Cervone M., Fichi G., Lami A., Lanza A., Damiani G.M., Perucci S. 2016. Internal and external parasitic infections of pet reptiles in Italy. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 26: 122-130. https://doi.org/10.5818/1529-9651-26.3-4.122

- Chang L., Jacobson E.R. 2010. Inclusion body disease, a worldwide infectious disease of boid snakes: a review. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 19: 216-225. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jepm.2010.07.014

- Chiodini R.J., Holdeman L.V., Gandelman A.L. 1983. Infectious necrotic hepatitis caused by an unclassified anaerobic bacillus in the water snake. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 93: 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9975(83)90010-5

- Costa M. 1966. The present stage of knowledge of mesostigmatic mites in Israel (Acari, Mesostigmata). Israel Journal of Zoology, 15: 69-82.

- Daltry J.C., Bloxam Q., Cooper G., Day M.L., Hartley J., Henry M., Lindsay K., Smith B.E. 2001. Five years of conserving the 'world's rarest snake′, the Antiguan racer Alsophis antiguae. Oryx, 35: 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3008.2001.00169.x

- DeNardo D.F., Wozniak E.J. 1997. Understanding the snake mite and current therapies for its control. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Conference of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians, 1997, pp. 137-147.

- Dhooria M.S. 2016. Fundamentals of Applied Acarology. Singapore: Springer. pp. 470. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1594-6

- Dik B. 2012. Türkiye'de Bir Su Yılanında (Natrix tessellata, Laurente 1768) (Reptilia: Squamata: Colubridae) ilk Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais, 1844) Olgusu. Turkiye Parazitolji Dergisi, 36: 112-115. https://doi.org/10.5152/tpd.2012.27

- Dipineto L., Raia P., Varriale L., Borrelli L., Botta V., Serio C., Capasso M., Rinaldi L. 2018. Bacteria and parasites in Podarcis sicula and P. sicula klemmerii. BMC Veterinary Research, 14: 392. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1708-5

- Divers S.J., Stahl S.J. 2019. Mader's Reptile And Amphibian Medicine And Surgery, Third Edition, Saint Louis: Elsevier. pp. 1537.

- Domrow R. 1963. New records and species of Austromalayan laelapid mites. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, 88: 199-220

- Domrow R. 1974. Miscellaneous mites from Australian vertebrates. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, 99: 15-35.

- Domrow R. 1985. Species of Ophionyssus Mégnin from Australian lizards and snakes (Acari: Dermanyssidae). Journal of the Australian Entomological Society, 24: 149-153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-6055.1985.tb00213.x

- Domrow R. 1988. Acari Mesostigmata parasitic on Australian vertebrates: an annotated checklist, keys and bibliography. Invertebrate Taxonomy, 1: 817-948. https://doi.org/10.1071/IT9870817

- Domrow R., Heath, A.C.G., Kennedy, C. 1980. Two new species of Ophionyssus (Acari : Dermanyssidae) from New Zealand lizards. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 7: 291-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014223.1980.10423790

- Dugès A. 1834. Recherches sur l′Ordre des Acariens. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, 2: 18-63 + Plates 7-8.

- Er-Rguibi O., Laghzaoui E.-L., Aglagane A., Kimdil L., Stekolnikov A.A., Abbad A., El Mouden E.H. 2023. New locality and host records of mites and ticks (Chelicerata: Acari) parasitizing lizards of Morocco. Acarologia, 63: 464-479. https://doi.org/10.24349/j4lz-jxdk

- Evans G.O., Till W.M. 1966. Studies on the British Dermanyssidae (Acari: Mesostigmata). Part II Classification. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology, 14: 109-370.

- Fain A. 1962. Les acariens mesostigmatiques ectoparasites des serpents. Bulletin de l′Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, 38: 1-149.

- Fain, A., Bannert B. 2000. Two new species of Ophionyssus Mégnin (Acari: Macronyssidae) parasitic on lizards of the genus Gallotia Boulenger (Reptilia: Lacertidae) from the Canary Islands. International Journal of Acarology, 26: 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647950008683634

- Feider Z., Solomon L. 1963. Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais) 1844 (Acari) o nouă specie pentru R.P.R. parazită pe şerpi. Studii și Cercetări Științifice Academia R.P. Române Filiala Iași. Biologie și Științe Agricole, 14: 281-286.

- Ferreira da Silva A., Teixeira Pinto Z., Hidalgo Teixeira R., Armando Cunha R., Carriço C., Leal Caetano R., Salles Gazeta G., Amorim M. 2018. First record of Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais) (Acari: Macronyssidae) on Python reticulatus (Schneider) (Pythonidae) in Brazil. EntomoBrasilis, 11: 41-44. https://doi.org/10.12741/ebrasilis.v11i1.768

- Fitzgerald K.T. 2019. Acariasis. In: Divers S.J., Stahl S.J. (Eds.). Mader's Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, third Edition. Saint Louis: Elsevier. p. 1290-1291. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-48253-0.00139-2

- Fitzgerald K.T., Vera R. 2006. Acariasis. In: Mader D.R. (Ed.). Reptile Medicine and Surgery. Saint Louis: Elsevier. p. 720-738. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-72-169327-X/50047-X

- Fonseca F. 1933. Presença do Ophionyssus serpentium (Hirst, 1915) (Acarina, Dermanyssidae) no serpentaria do Instituto Butantan. Memórias do Instituto Butantan, 7: 145-146.

- Fonseca F. 1948. A monograph of the genera and species of Macronyssidae Oudemans, 1936 (synom.: Liponissidae Vitzthum, 1931) (Acari). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 118: 249-334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1948.tb00378.x

- Fonseca F. 1954. Notas de acarologia. XXXVI. Aquisiçôes novas para a fauna Brasileira de ácaros haematófagos (Acari, Macronyssidae). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 1: 79-92.

- Fuantos-Gámez B.A, Romero-Núñez C., Sheinberg-Waisburd G., Bautista-Gómez L.G, Yarto-Jaramillo E., Heredia-Cardenas R., Miranda-Contreras L. 2020. Successful treatment of Ophionyssus natricis with afoxolaner in two Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivittatus). Veterinary Dermatology, 31: 496-498. https://doi.org/10.1111/vde.12898

- Garrett C.M., Harwell G. 1991. Loreal pit impaction in a black speckled palm-pitviper (Bothriechis nigroviridis). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 22: 249-251.

- Gervais F.L.P. 1844. Acarides. In: Walckenaer C.A. (Ed.). Histoire Naturelle des Insectes. Aptères. III. Paris: Roret. p. 132-288.

- Gobble J. 2022. Oral Fluralaner (Bravecto®) use in the control of mites in 20 Ball Pythons (Python regius). Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 32: 111-112. https://doi.org/10.5818/JHMS-D-21-00003

- Goldberg S.R., Bursey C.R. 1991. Integumental lesions caused by ectoparasites in a wild population of the Side-blotched lizard Uta stansburiana. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 27: 68-73. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-27.1.68

- Gomes-Almeida, B.K., Pepato, A.R. 2021. A new genus and new species of macronyssid mite (Mesostigmata: Gamasina: Macronyssidae) from Brazilian caves including molecular data and key for genera occurring in Brazil. Acarologia, 61: 501-526. https://doi.org/10.24349/acarologia/20214447

- Hallas T.E. 1978. Fortegnelse over Danske mider (Acari). Entomologiske Meddelelser, 46: 27-45.

- Hassl A.R. 2016. Ticks and mites parasitizing free-ranging reptiles in Austria - with an identification key to Central European herpetophagous Acarina. Herpetozoa, 29: 77-83.

- Heath A.C.G. 1986. First occurrence of the reptile mite, Ophionyssus natricis (Acari: Dermanyssidae) in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 34: 78. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.1986.35304

- Huchzermeyer E.W. 2003. Crocodiles. Biology, Husbandry and Diseases. Wallingford: CAB Publishing. pp. 353. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996561.0000

- Jacobson E.R. 1984. Immobilization, blood sampling, necropsy techniques and diseases of crocodilians: a review. Journal of Zoo Animal Medicine, 15: 38-45. https://doi.org/10.2307/20094678

- Keegan, H.L. 1956. Ectoparasitic lealaptid and dermanyssid mites of Egypt, Kenya and: the Sudan, primarily based on Namru 3 Collections, 1948 - 1953. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 31: 199-272 + Plates I-XIII.

- Keskin A. 2021. Occurrence of Ophionyssus natricis (Acari: Macronyssidae) on the captive corn snake, Pantherophis guttatus, (Squamata: Colubridae) in Turkey. Acarological Studies, 3: 89-95. https://doi.org/10.47121/acarolstud.907114

- Khaire A., Khaire N., Joshi P.V., Bhat, H.R. 1987. An outbreak of infestation of Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais, 1844) in the snake park at Poona, India. The Snake, 19: 70-71.

- Leslie A.J., Lovely C.J., Pittman J.M. 2011. A preliminary disease survey in the wild Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) population in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association, 82: 155-159. https://doi.org/10.4102/jsava.v82i3.54

- Ma L.-M., Bai X.-L. 2012. Discovery of the genus Ophionyssus Mégnin in China and description of a new species (Acari: Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae). Acta Arachnologica Sinica, 21: 83-86.

- Magnusson W.E. 1985. Habitat selection, parasites and injuries in Amazonian crocodilians. Amazoniana, 9: 193-204.

- Manoj R.R.S., Latrofa M.S., Mendoza‑Roldan J.A., Otranto D. 2021. Molecular detection of Wolbachia endosymbiont in reptiles and their ectoparasites. Parasitology Research, 120: 3255-3261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-021-07237-1

- Mariana A., Vellayan S., Halimaton I., Ho T.M. 2011. Acariasis on pet Burmese python, Python molurus bivittatus in Malaysia. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 4: 227-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60075-8

- Markov G.S., Bogdanov O.P. 1960. Helminths and mites – parasites of snakes in Central Asia. Uzbek biological journal, 1: 35-41.

- Markov G.S., Ivanov V.P., Kryuchkov G.P., Lukianova Zh.F., Nikulin V.P., Chernobay V.F. 1964. Protozoan and parasitic mites of reptiles from the Caspian region. Scientific notes of the Volgograd State Pedagogical Institute Named after A.S. Serafimovich, 16: 106-110. [In Russian]

- Maslova I.V., Dochevoy Y.E. 2016. A case of protocooperation between the pitviper Gloydius ussuriensis and the ground beetle Carabus granulatus telluris. Russian Journal of Herpetology, 23: 231-234. https://doi.org/10.30906/1026-2296-2016-23-3-231-234

- Mauri R. 1967. Acaros Mesostigmata parásitos de vertebrados de la República Argentina. Segundas Jornadas Entomoepidemiológicas Argentinas, 1: 65-73.

- Maxwell C. 2022. Snake Mites: What They Are and How to Treat. Available from: https://a-z-animals.com/blog/snake-mites-what-they-are-and-how-to-treat. [13 Oct 2023]

- McClain D., Dana A.N., Goldenberg G. 2009. Mite infestations. Dermatologic Therapy, 22: 327-346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01245.x

- Mégnin P. 1884a. Etude d'un acarien parasite des serpents, l′Ophionyssus natricis, P. Gervais, et de son action. Compte Rendus des Séances et Mémoires de la Société de Biologie, Paris, 35: 614-619.

- Mégnin P. 1884b. Étude sur l′Ophionyssus natricis P. Gervais. Bulletin de la Societe Zoologique de France, 9: 107-13 + Plate II.

- Mehl R. 1979. Checklist of Norwegian ticks and mites (Acari). Fauna Norvegica, Series B, 26, 31-45.

- Mendoza-Roldan J.A.R. 2019 Acarofauna of Reptiles and Amphibians of Brazil: Morphological and Molecular Studies and Pathogens Research [Doctor Thesis], University of Sao Paulo. pp. 461.

- Mendoza-Roldan J.A., Colella V., Lia R.P., Nguyen V.L., Barros-Battesti D.M., Iatta R., Dantas-Torres F., Otranto D. 2019. Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) in ectoparasites and reptiles in southern Italy. Parasites & Vectors, 12; 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3286-1

- Mendoza-Roldan J.A., Modry D., Otranto D. 2020a. Zoonotic parasites of reptiles: A crawling threat. Trends in Parasitology, 36: 677-687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.04.014

- Mendoza-Roldan J., Ribeiro S.R. Castilho-Onofrio V., Grazziotin F.G., Rocha B., Ferreto-Fiorillo B., Pereira J.S., Benellig G., Otranto D., Barros-Battesti D.M. 2020b. Mites and ticks of reptiles and amphibians in Brazil. Acta Tropica, 208: 105515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105515

- Mendoza-Roldan J.A., Mendoza-Roldan M.A., Otranto D. 2021. Reptile vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, 15: 132-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2021.04.007

- Mendoza‑Roldan J.A., Napoli E., Perles L., Marino M., Spadola F., Berny P., España B., Brianti E., Beugnet F., Otranto D. 2023. Afoxolaner (NexGard®) in pet snakes for the treatment and control of Ophionyssus natricis (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae). Parasites & Vectors, 16: 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05611-1

- Mendyk R.W. 2015. Preliminary notes on the use of the predatory soil mite Stratiolaelaps scimitus (Acari: Laelapidae) as a biological control agent for acariasis in lizards. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 25: 24-27. https://doi.org/10.5818/1529-9651-25.1.24

- Metaxa L. 1823. Monographia de Serpenti di Roma e Suoi Contorni. Rome: Nella Stamperia de Romanis. pp. 48. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.5101

- Micherdzinski W. 1980. Eine Taxonomische Analyse der Familie Macronyssidae Oudemans, 1936. I. Subfamilie Ornithonyssinae Lange, 1958 (Acarina, Mesostigmata). Warszawa: Polska Akademia Nauk. pp 263.

- Miranda R.J., Cleghorn J.E., Bermúdez S.E., Perotti, M.A. 2017. Occurrence of the mite Ophionyssus natricis (Acari: Macronyssidae) on captive snakes from Panama. Acarologia, 57: 365-368. https://doi.org/10.1051/acarologia/20164161

- Miron L., Ivan O. 2003. O nouă species a genului Ophionyssus Mégnin (1844) (Acari, Gamasida, Macronyssidae), ectoparazit pe Vipera ursinii. Revista Scientia Parasitologica, 4: 172-174.

- Moraza M.L., Irwin N.R., Godinho R., Baird S.J.E., de Bellocq J.G. 2009. A new species of Ophionyssus Mégnin (Acari: Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) parasitic on Lacerta schreiberi Bedriaga (Reptilia: Lacertidae) from the Iberian Peninsula, and a world key to species. Zootaxa, 2007: 58-68. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2007.1.3

- Nieri-Bastos F.A., Labruna M.B., Marcili A., Durden, L.A., Mendoza-Uribe, L., Barros-Battesti D.M. 2011. Morphological and molecular analysis of Ornithonyssus spp. (Acari: Macronyssidae) from small terrestrial mammals in Brazil. Experimental and Applied Acarology, 55: 305-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-011-9475-z

- doi 10.1007/s10493-011-9475-z

- Norval G., Halliday B., Sih A., Sharrad R.D., Gardner M.G. 2020. Occurrence of the introduced snake mite, Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais, 1844), in the wild in Australia. Acarologia, 60: 559-565. https://doi.org/10.24349/acarologia/20204385

- doi: 10.24349/acarologia/20204385 https://doi.org/10.24349/acarologia/20204385

- Norval G., Halliday B., Sharrad R.D., Gardner M.G. 2021. Additional instances of snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis) parasitism on sleepy lizards (Tiliqua rugosa) in South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 145: 183-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2021.1934629

- Oliver J.H. 1971. Parthenogenesis in mites and ticks (Arachnida: Acari). American Zoologist, 11: 283-299. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/11.2.283

- Oudemans A.C. 1901. Notes on Acari. Third Series. Tijdschrift der Nederlandsche Dierkundige Vereeniging, 7: 50-88 + Plates I-III.

- Page L.A. 1966. Diseases and infections of snakes: a review. Bulletin of the Wildlife Disease Association, 2: 111-126. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-2.4.111

- Paredes-León R., García-Prieto L., Guzmán-Cornejo C., León-Regagnon V., Pérez T.M. 2008. Metazoan parasites of Mexican amphibians and reptiles. Zootaxa, 1904: 1-166. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1904.1.1

- Partyka J.K. 2019. Parasites and People: Crocodile Parasite Interactions in Human Impacted Areas of Belize [Master's Thesis]. Ås: Norwegian Journal of Life Sciences, pp. 48.

- Pawełczyk O., Pająk C., Solarz K. 2016. The risk of exposure to parasitic mites and insects occurring on pets in Southern Poland. Annals of Parasitology, 62: 337-344.

- Pereira A.C., Colli G.R. 2023. Landscape features affect caiman body condition in the middle Araguaia River floodplain. Animal Conservation, 26: 531-545. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12841

- Phisalix M. 1914. Sur une Hémogrégarine nouvelle, parasite de Boodon fuliginosus Boïe, et ses forms de multiplication endogène. Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique, 7: 358-360.

- Radford C.D. 1950. The mites (Acarina) parasitic on mammals, birds and reptiles. Parasitology, 40: 366-394. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000018230

- Radovsky F.J. 1971. Ophionyssus natricis (Gervais). Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society, 21: 13-14.

- Radovsky F.J. 2010. Revision of Genera of the Parasitic Mite Family Macronyssidae (Mesostigmata: Dermanyssoidea) of the World. West Bloomfield: Indira Publishing House. pp. 170.

- Rataj A.V., Lindtner-Knific R., Vlahović K., Mavri U., Dovč A. 2011. Parasites in pet reptiles. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 53: 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-53-33

- Reeves W.K., Dowling A.P.G., Dasch G.A. 2006. Rickettsial agents from parasitic Dermanyssoidea (Acari: Mesostigmata). Experimental and Applied Acarology, 38: 181-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-006-0007-1

- doi 10.1007/s10493-006-0007-1

- Reinert W., Brandstätter F. 1993. Zur Biologie der Milbe Ophionyssus natricis. Salamandra, 29: 248-257.

- Reptiles Cove. 2022. Acariasis Caused by Snake Mites: Everything You Need to Know. Available from https://reptilescove.com/care/snakes/acariasis. [13 Oct 2023].

- Rimbaud E., Pineda N., Luna L., Zepeda N., Rivera G. 2006. Primer reporte de Ophionyssus natricis (Arthropoda, Acarina, Macronyssidae, Gervais 1953) parasitando Boa constrictor constrictor en Nicaragua. Boletín de Parasitologia Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria Universidad Nacional Costa Rica, 7 (2): 1.

- Rodriguez M.L., Lazcano D. 1992. Primer reporte de ácaro Ophionyssus natricis (Acarina: Macronyssidae) para México. Southwestern Naturalist, 37: 426. https://doi.org/10.2307/3671798

- Rotter J. 1963. Die Warane. Wittenberg: Ziemsen Verlag. pp. 76.

- Sabu L., Devada K., Subramanian H., Cheeran J.V. 2002. Diploscapter coronata (Cobb, 1893) infestation in captive snakes. Zoos' Print Journal, 17: 954-956. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.ZPJ.17.12.954-6

- Salazar M.M. 2014. Determination y Control Parasitario en iguana verde (Iguana iguana) Mantenida Cautivero [Master's thesis]. Mexico: Universidad del Mar. pp. 104.

- Santana-Hernández K.M., Orós J., Priestnall S.L., Monzón-Argüello C., Rodríguez-Ponce E. 2021. Parasitological findings in the invasive California kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae) in Gran Canaria, Spain. Parasitology, 148: 1345-1352. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182021000871

- Schilliger L.H., Morel D., Bonwitt J.H., Marquis O. 2013. Cheyletus eruditus (Taurrus®): An effective candidate for the biological control of the snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 44: 654-659. https://doi.org/10.1638/2012-0239R.1

- Schroeder C.R. 1934. The snake mite (Ophionyssus serpentium Hirst). Journal of Economic Entomology, 28: 1004-1014. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/27.5.1004

- Schultz H. 1975. Human infestation by Ophionyssus natricis snake mite. British Journal of Dermatology, 93: 695-697. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb05120.x

- Schumacher J., Jacobson E.R. Homer B.L., Gaskin J.M. 1994. Inclusion body disease in boid snakes. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 25: 511-524.

- Schweizer J. 1961. Die Landmilben der Schweiz (Mittelland, Jura und Alpen). Parasitiformes Reuter. Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturfoorschenden Gesellschaft, 84: 1-207.

- Shulov A. 1957. Additions to the fauna of Acarina of Israel (excluding ticks and gall mites). Bulletin of the Research Council of Israel, 6B: 233-238.

- Simonov E., Zinchenko V. 2010. Intensive infestation of Siberian pit-viper, Gloydius halys halys by the common snake mite, Ophionyssus natricis. North-Western Journal of Zoology, 6: 134-137.

- Šlapeta J., Modrý D., Johnson R. (2018) Reptile parasitology in health and disease. In: Doneley B., Monks D., Johnson R., Carmel B. (eds) Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., p. 425-440. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118977705.ch31

- Su H.-Y., Gao X.-P., Bai X.-L. 2010. Investigation on parasitic gamasid on Phrynocephalus przewalskii (Strauch, 1876) in Ningxia. Endemic Diseases Bulletin, 25: 4-5.

- Sumaira, Bukhari M.S., Iram M., Javid A., Hussain A., Ali W., Rehman K.U., Andleeb S., Baboo I., Khalid N. 2020. Seasonal variation in ecdysis process and parasitic prevalence in Indian Rock Python (Python molurus). Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 52: 2341-2346. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/20190417060401

- Tarshis I.B. 1960. Control of the snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis), other mites, and certain insects with the sorptive dust, SG 67. Journal of Economic Entomology, 53: 903-908. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/53.5.903

- Tellez M. 2013. A checklist of host-parasite interaction of the order Crocodylia. University of California Publications in Entomology, 136: 1-376. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520098893.003.0001

- Thaler R., Ortega Z., Ferreira V.L. (2022) Extrinsic traits consistently drive microhabitat decisions of an arboreal snake, independently of sex and personality. Behavioral Processes, 199 (104649): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2022.104649

- Thomasson V., Blouin-Demers G. 2015. Using habitat suitability models considering biotic interactions to inform critical habitat delineation: An example with the eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos) in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Wildlife Biology and Management, 4: 1-17.

- Till W.M. 1957. Mesostigmatic mites living as parasites of reptiles in the Ethiopian region (Acarina: Laelaptidae). Journal of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa, 20: 120-143.

- Uetz P., Freed P., Aguilar R., Reyes F., Hošek J. 2023. The Reptile Database. Available from http://www.reptile-database.org. [13 Oct 2023].

- Vasiliev D.B., Balakina O.S. (undated) Hematological studies in infectious and parasitic diseases of a rare species of pythons, Morelia boeleni. Available from http://www.dompitomci.ru/doc/conf/2097.html [19 Oct 2023]

- Vitzthum H. 1943. Dr. H. G. Bronns Klassen und Ordnungen des Tierreichs. 5 Band: Arthropoda. IV. Abteilung: Arachnoidea. 5. Buch. Acarina. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Becker & Erler Kom. pp. 1011.

- Whan S.-T. 1966. Studies on the fauna of Korean Mites (Gamasoidea) (I). Saengmulhak Biology, 5 (3): 27-33 (not seen, cited by Beron, 2014).

- Wiechert J.M. 2007. Infection of Hermann's tortoises, Testudo hermanni boettgeri, with the Common Snake Mite, Ophionyssus natricis. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 17: 53-54. https://doi.org/10.5818/1529-9651.17.2.53

- Womersley H. 1956. On some new Acarina-Mesostigmata from Australia, New Zealand and New Guinea. Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Zoology, 42: 505-599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1956.tb02218.x

- Wozniak E.J., DeNardo D.F. 2000. The biology, clinical significance and control of the common snake mite, Ophionyssus natricis, in captive reptiles. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 10: 4-10. https://doi.org/10.5818/1529-9651-10.3.4

- Yunker C.E. 1956. Studies on the snake mite, Ophionyssus natricis, in nature. Science, 124: 979-980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.124.3229.979

- Zemskaya A.A. 1951. Biology and development of the mites from the family Dermanyssidae parasitic on reptiles in the connection with the problem of their mode of parasitism. Bulletin de la Societe des Naturalistes Moscow Biologie, 56: 42-57. [In Russian].

- Zhang M.-Y., Uchikawa K. 1993. Ocurrence of Ophionyssus natricis on zoo snakes in Japan (Mesostigmata, Macronyssidae). Journal of the Acarological Society of Japan, 2: 75-78. https://doi.org/10.2300/acari.2.75

2024-01-27

Date accepted:

2024-04-16

Date published:

2024-05-06

Edited by:

Roy, Lise

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2024 Orlova, Maria V.; Halliday, Bruce; Reeves, Will K.; Doronin, Igor V.; Mishchenko, Vladimir A.; Vyalykh, Ivan V. and Kidov, Artem A.

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)