Flat mites (Tenuipalpidae) from Bahia state, Northeastern Brazil - a checklist including new records and an illustrated key to species

Nascimento, Renata S.  1

; Souza, Kaélem S.

1

; Souza, Kaélem S.  2

; Melo, Elisangela A. S. F.

2

; Melo, Elisangela A. S. F.  3

; Tassi, Aline D.

3

; Tassi, Aline D.  4

; Castro, Elizeu B.

4

; Castro, Elizeu B.  5

; Navia, Denise

5

; Navia, Denise  6

; de Mendonça, Renata S.

6

; de Mendonça, Renata S.  7

; Ochoa, Ronald

7

; Ochoa, Ronald  8

and Oliveira, Anibal R.

8

and Oliveira, Anibal R.  9

9

1✉ Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC), Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil.

2Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC), Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil.

3Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC), Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil.

4Tropical Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Homestead, USA.

5Departamento de Zoologia e Botânica, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil.

6CBGP, INRAE, CIRAD, Institut Agro, IRD, Univ Montpellier, Avenue du Campus Agropolis, Campus de Baillarguet, Montferrier-sur-Lez, France.

7Faculdade de Agronomia e Medicina Veterinária, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brazil.

8Systematic Entomology Laboratory (SEL), Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Beltsville Agricultural Research Centre (BARC), Beltsville, MD, USA.

9Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC), Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil & Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC), Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil.

2023 - Volume: 63 Issue: 3 pages: 619-636

https://doi.org/10.24349/b4og-onlsOriginal research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

The flat mite family Tenuipalpidae (Trombidiformes: Tetranychoidea) is one of the most important families of plant-feeding mites world-wide (Gerson 2008; Moraes and Flechtmann 2008). The family has approximately 1,100 described species in 41 genera and is distributed worldwide (Mesa et al. 2009; Castro et al. 2022a). Studies of flat mites in Brazil began with Bondar (1928), who reported the first two species for the country from Bahia, Brevipalpus californicus (Banks, 1904) as ''Tenuipalpus californicus'' and Brevipalpus obovatus Donnadieu, 1875 as ''Tenuipalpus bioculatus''. Currently, 40 Tenuipalpidae species have been recorded from Brazil, and prior to this study, only 11 species had been reported from Bahia, in the genera Brevipalpus, Tenuipalpus, Dolichotetranychus, and Raoiella (Castro et al. 2022a).

Several tenuipalpid species are considered pests of many crops worldwide (Mesa et al. 2009; Beard et al. 2013, 2018). They may cause damage directly by feeding on host plant tissues, and indirectly through the transmission of plant viruses (Childers et al. 2003; Mesa et al. 2009; Beard et al. 2015; Lillo et al. 2021). Due to their association with phytoviruses, species in the genus Brevipalpus have historically received the most attention inside the family (Mesa et al. 2009; Beard et al. 2015). Some diseases caused by viruses transmitted by Brevipalpus (VTBs) have already been reported in Bahia (Kitajima 2020), such as the citrus leprosis virus C (CiLV-C) (Bastianel et al. 2010; Ramos-González et al. 2016), the passion fruit green spot virus (PFGSV) (Santos Filho et al. 1999; Ramos-González et al. 2020) and the coffee ringspot virus (CoRSV) (Almeida and Figueira 2014; Ramalho et al. 2014), along with some suspected samples of zonate chlorosis in citrus (Kitajima 2020).

Due to their morphological similarity, Brevipalpus species, including those of the greatest economic importance, have consistently been confused and misidentified (Welbourn et al. 2003). Poor descriptions and illustrations as well as a lack of critical morphological studies have rendered the taxonomy of Brevipalpus species a puzzle (Beard et al. 2015). However, recently the taxonomic confusion surrounding the most important species belonging to the Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes) species complex were addressed with detailed morphological studies (Beard et al. 2013, 2015). Following from this, taxonomists worldwide have directed efforts towards accurately identifying Brevipalpus species and consequently to determining the distributions of certain species.

The Bahia state territory is located in the Northeastern region of Brazil, that includes three natural biomes that are characterized by different physical and biological characteristics, such as soil, rainfall, and vegetation (Santos et al. 2018): (1) the ''Cerrado'', which is considered the Brazilian savannah (Ratter et al. 1997); (2) the ''Caatinga'', a typical, semi-arid biome (Sampaio 1995; Costa et al. 2007); and (3) the Atlantic Forest, a dense ombrophilous forest in the coastal region of the state (Câmara 2003).

This paper presents a compilation of the tenuipalpid species reported from Bahia, including published and five new species records from twenty-nine plant species/varieties in fifteen municipalities, along with an illustrated identification key to all species and a map locating each record in the biomes where they were collected.

Materials and methods

The checklist of the tenuipalpid mites reported from the Bahia state territory includes all the species records published in periodical journals, annals, and/or books, and newly identified specimens collected in the present study. The acquisition of published records was based on internet searches, the catalog of Mesa et al. (2009), and the database of Castro et al. (2022a). All the records were confirmed through direct consultation with original publications, voucher specimens and the type image reference at the Flat Mites of the World.

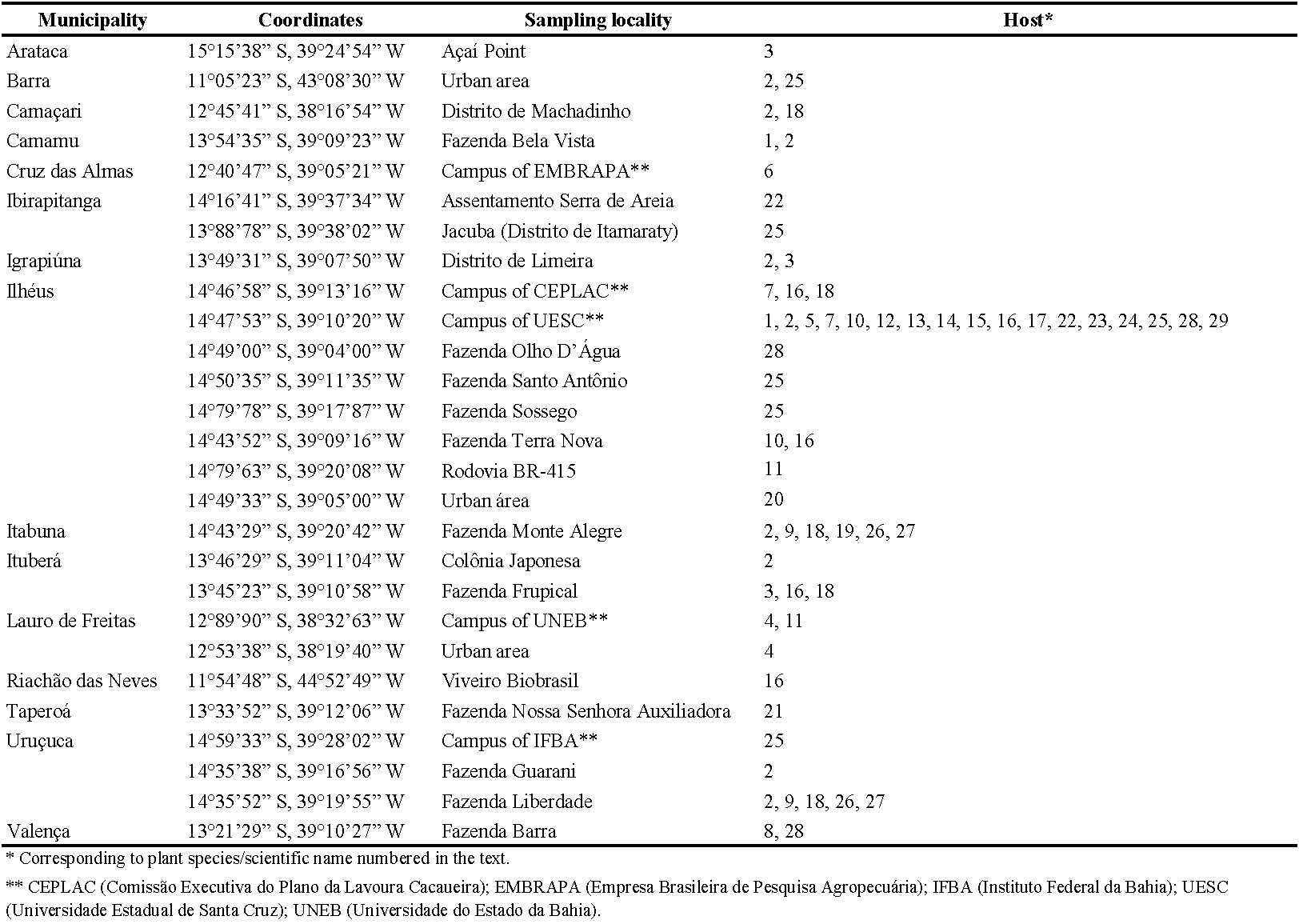

Mite specimens collected between March 2007 and November 2021 from fifteen municipalities in the Bahia state territory, northeastern Brazil were identified for the present study. Samples consisted of leaves and branches of twenty-nine plant species/varieties in seventeen families: Anarcadiaceae – (1) Spondias mombin; Arecaceae – (2) Cocos nucifera, (3) Euterpe oleracea, (4) Veitchia merrillii; Boraginaceae – (5) Cordia trichotoma; Bromeliaceae – (6) Ananas comosus; Euphorbiaceae – (7) Hevea brasiliensis; Heliconiaceae – (8) Heliconia bihai, (9) Heliconia psittacorum x H. spathocircinada cv. Golden Torch, (10) Heliconia rostrata, (11) Heliconia sp., (12) Heliconia sp. var. Irish Red; Lecythidaceae – (13) Lecythis lurida; Malpighiaceae – (14) Malpighia emarginata; Malvaceae – (15) Malvaviscus arboreus, (16) Theobroma cacao, (17) Theobroma grandiflorum; Musaceae – (18) Musa sp.; Myrtaceae – (19) Psidium guajava; Orchidaceae – (20) Phalaenopsis sp.; Oxalidaceae – (21) Averrhoa carambola; Passifloraceae – (22) Passiflora edulis; Rubiaceae – (23) Coffea arabica, (24) Morinda citrifolia; Rutaceae – (25) Citrus sp.; Zingiberaceae – (26) Alpinia purpurata var. Rose, (27) Alpinia purpurata var. Red, (28) Etlingera elatior, (29) Zingiber spectabile. Numbers in parenthesis referred to above for each plant species are presented in Table 1 with the respective sampling localities.

Leaves and branches samples collected on the field were placed in paper and/or polythene bags, and brought to the laboratory in polystyrene boxes containing Gelox, where they were stored at 10 °C for up to five days before analysis. Vegetal parts were inspected under a stereomicroscope (Leica EZ4) and all the tenuipalpids found were mounted in Hoyer's medium (Krantz and Walter 2009). Mites were identified under Phase Contrast (PC) and Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) microscopy (Leica DM 2500 and Zeiss Imager D2). Voucher specimens were deposited in the Acarological Collection of Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC), Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil (AC-UESC).

The species names adopted in the checklist are those of Castro et al. (2022a), although alternative names and/or synonymies referred to in the publications are also presented. References to published records relating to each species are given under ''Records in Bahia'' in chronological order, followed by the first page the species record was provided in the original publication. Information concerning the sampling locality, plant species, month and year of collection, number of individuals, and the sex of all the tenuipalpids examined and identified in the present study are provided under ''Specimens examined''. When necessary, comments on both the identifications in the published records and of the specimens identified in the present study, are provided under ''Remarks''. To help identify all the species presented in the checklist, an illustrated identification key for females, partially based on Beard et al. (2015) and Castro et al. (2022b), is provided, with photographs of distinctive characters referred to in the text. The photographs used in the illustrated key were obtained from the material collected in the present study, and from the Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz (UESC) and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reference collections.

Results

Thirty-two papers to date have reported tenuipalpids from Bahia, and refer to a total of 11 species. Approximately 72% of those papers refer to the genus Brevipalpus, 16% to Tenuipalpus, 9% to Raoiella, and 3% to Dolichotetranychus. Five new species records were identified for the state, and are marked with an asterisk (*) in the list below. A total of thirteen species in four genera were identified in the present study, with 8 of these having been previously recorded. There were 3 previously recorded species that were not recollected in the present study, Brevipalpus obovatus, Tenuipalpus odoratus, and Tenuipalpus orchidofilo. Both published and new records are provided in the checklist below. The distribution of the records in Bahia are presented in relation to the three biomes in Figure 1.

Genus Brevipalpus Donnadieu, 1875

Brevipalpus californicus (Banks, 1904) sensu lato

Records in Bahia. Bondar, 1928: 39 (as Tenuipalpus californicus); Silva et al. 2022: 1; present study.

Specimens examined. UESC, ex. H. brasiliensis, Nov 2021 (2 ♀♀).

Remarks. The californicus group is composed of species of various morphological types identified as B. californicus sensu lato in Beard et al. (2013), and it has been accepted that this taxon name represents a species complex that is currently under revision (Tassi and Ochoa, personal communication). The morphology of the only two females collected in the present study is similar to the original description by Banks (1904) and to the photos of B. californicus sensu lato presented by Beard et al. (2013).

*Brevipalpus feresi Ochoa & Beard, 2015

Records in Bahia. Present study.

Specimens examined. Limeira, ex. E. oleracea, Jun 2017 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. C. arabica, Aug 2017 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. H. rostrata, Aug 2017 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. C. arabica, Nov 2017 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. M. emarginata, Nov 2017 (3 ♀♀); UESC, ex. M. emarginata, Jan 2018 (1 ♀).

Remarks. The morphology of females collected in the present study is similar to the original description by Beard et al. (2015), except for the dorsal setae of the opisthosoma, which are slightly shorter than the original description.

Brevipalpus obovatus Donnadieu, 1875

Records in Bahia. Bondar, 1928: 39 (as Tenuipalpus bioculatus); Flechtmann, 1976: 59; Cavalcante et al. 2006: 1; Laranjeira et al. 2011: 17; Noronha and Cavalcante 2011: 453.

Remarks. Some works suggest that there is intraspecific variation between specimens previously classified as B. obovatus, as was found for the B. phoenicis and B. californicus species complexes, which could also indicate a complex of species (Mesa et al. 2009; Navia et al. 2013; Alves et al. 2019). This species was not collected in the present study.

*Brevipalpus papayensis Baker, 1949

Records in Bahia. Present study.

Specimens examined. UESC, ex. C. arabica, Aug 2017 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. H. rostrata, Aug 2017 (2 ♀♀); IFBA, ex. Citrus sp., Sep 2017 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. C. arabica, Nov 2017 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. M. emarginata, Nov 2017 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. M. emarginata, Jan 2018 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. M. citrifolia, Jul 2021 (1 ♀).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the original description by Baker (1949) and to the redescription presented in Beard et al. (2015); however, some specimens showed slight variation in the bands with mixed orientation on the genital plate compared with that presented in the latter work.

Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes, 1939)

Records in Bahia. Flechtmann and Abreu 1973: 249; Flechtmann, 1976: 58; Moraes and Flechtmann 1981: 183; Flechtmann and Arleu 1984: 124; Noronha et al. 1997: 373; Santos Filho et al. 1999: 5; Ribeiro et al. 2001: 2022; Fiaboe et al. 2007: 9; Oliveira et al. 2007: 257; Almeida et al. 2010: 1; Laranjeira et al. 2011: 17; Noronha and Cavalcante 2011: 453; Silva et al. 2012a: 1; Silva et al. 2012b: 17; Navia et al. 2013: 6; Almeida and Figueira 2014: 1; Laranjeira et al. 2015: 1; present study.

Specimens examined. F. Terra Nova, ex. H. rostrata, Sep 2007 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. Z. spectabile, Sep 2007 (1 ♀); F. Barra, ex. E. elatior, Nov 2007 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. E. elatior, May 2007 (1 ♀); F. Frupical, ex. Musa sp., Apr 2007 (2 ♀♀); UESC, ex. Heliconia sp. var.Irish Red, Sep 2007 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. T. grandiflorum, Jul 2021 (1 ♀).

Remarks. All the published records under the taxon name B. phoenicis in Bahia were provided before the publication of Beard et al. (2015), and should be considered questionable due to synonymies and historic misidentifications. In this way these records should be considered as B. phoenicis sensu lato. All the females collected in the present study have similar morphology to the redescription of B. phoenicis sensu stricto provided by Beard et al. (2015).

Brevipalpus tuberellus De Leon, 1960

Records in Bahia. Alves et al. 2019: 2184; present study.

Specimens examined. CEPLAC, ex. Musa sp., Nov 2017 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. L. lurida, Mar 2018 (16 ♀♀, 1 DN, 11 PN, 7 LV).

Remarks. All the specimens of B. tuberellus included in the molecular phylogenetic analysis of Alves et al. (2019) and identified in the present study were collected from the municipality of Ilhéus by Kaélem S. Sousa. The morphology of the females is similar to the original description by De Leon (1960) and the redescription by Baker and Tuttle (1987).

Brevipalpus yothersi Baker, 1949

Records in Bahia. Arena et al. 2016: 27; Ramos-González et al. 2016: 14; Mineiro et al. 2018: 4; Silva et al. 2022: 1; present study.

Specimens examined. F. Santo Antônio, ex. Citrus sp., Mar 2007 (2 ♀♀, 1 DN, 1 PN, 2 LV); F. Frupical, ex. T. cacao, Apr 2007 (1 ♀); F. Liberdade, ex. A. purpurata verm., Apr 2007 (1 ♀, 1 DN, 1 PN); F. Liberdade, ex. A. purpurata rosa, Apr 2007 (1 ♀, 1 DN); F. Liberdade, ex. H. psittacorum x H. Spathocircinada cv., Apr 2007 (2 ♀♀); F. Olho D'Água, ex. E. elatior, May 2007 (2 ♀♀, 1 DN); F. Terra Nova, ex. T. cacao, May 2007 (1 ♀); F. Liberdade, ex. Musa sp., May 2007 (1 ♀); F. F. N. S. Auxiliadora, ex. A. carambola, Jul 2007 (1 ♀); F. Monte Alegre, ex. P. guajava, Oct 2007 (3 ♀♀, 2 DN); UESC, ex. Citrus sp., Sep 2011 (4 ♀♀); UESC, ex. T. cacao, Apr 2012 (1 ♀); A. Point, ex. E. oleracea, May 2016 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. C. nucifera, Aug 2017 (5 ♀♀, 5 DN, 2 PN); UESC, ex. Citrus sp., Aug 2017 (17 ♀♀); UESC, ex. E. elatior, Sep 2017 (1 ♀); IFBA, ex. Citrus sp., Sep 2017 (4 ♀♀); Jacuba (Itamarati), ex. Citrus sp., Sep 2017 (6 ♀♀); CEPLAC, ex. Musa sp., Nov 2017 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. H. rostrata, Nov 2017 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. C. trichotoma, Jan 2018 (11 ♀♀); UESC, ex. M. emarginata, Jan 2018 (1 ♀); A. Serra de Areia, ex. P. edulis, Jan 2018 (3 ♀♀); UESC, ex. L. lurida, Mar 2018 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. P. edulis, Mar 2018 (15 ♀♀); Urban area (Barra), ex. Citrus sp., May 2019 (48 ♀♀, 7 DN); UESC, ex. P. edulis, Jan 2021 (4 ♀♀, 3 DN, 5 PN, 5 LV); CEPLAC, ex. T. cacao, Apr 2021 (3 ♀♀, 2 LV); Rod. BR-415, ex. Heliconia sp., Jun 2021 (3 ♀♀, 1 DN, 2 LV); UESC, ex. M. arboreus, Jul 2021 (8 ♀♀); F. Sossego, ex. Citrus sp., Nov 2021 (1 ♀); V. Biobrasil, ex. T. cacao, Nov 2021 (15 ♀♀, 8 DN, 6 PN, 5 LV).

Remarks. The morphology of females collected in the present study is similar to the original description by Baker (1949) and to the redescription presented by Beard et al. (2015).

Genus Dolichotetranychus Sayed, 1938

Dolichotetranychus floridanus (Banks, 1900)

Records in Bahia. Sanches and Flechtmann 1982: 151; present study.

Specimens examined. EMBRAPA, ex. A. comosus, Aug 2016 (15 ♀♀).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the redescription presented in Baker and Pritchard (1956).

Genus Raoiella Hirst, 1924

Raoiella indica Hirst, 1924

Records in Bahia. Melo et al. 2018: 148; Nuvoloni et al. 2021: 1769; Nuvoloni et al. 2022: 1; present study.

Specimens examined. UNEB, ex. V. merrillii, Sep 2017 (16 ♂♂, 11 ♀♀); Urban area (L. de Freitas), ex. V. merrillii, Sep 2017 (18 ♂♂, 41 ♀♀); UNEB, ex. Heliconia sp., Sep 2017 (13 ♂♂, 36 ♀♀); Machadinho, ex. Musa sp., Sep 2017 (15 ♂♂, 18 ♀♀, 1 DN); Machadinho, ex. C. nucifera, Sep 2017 (31 ♂♂, 83 ♀♀, 5 DN, 6 PN); Urban area (Barra), ex. C. nucifera, May 2019 (1 ♂, 3 ♀♀).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the redescription presented by Beard et al. (2018).

Genus Tenuipalpus Donnadieu, 1875

*Tenuipalpus coyacus De Leon, 1957

Records in Bahia. Present study.

Specimens examined. F. Frupical, ex. E. oleracea, Apr 2007 (1 ♀); F. Liberdade, ex. C. nucifera, May 2007 (1 ♀); F. Bela Vista, ex. C. nucifera, Aug 2007 (23 ♀♀); C. Japonesa, ex. C. nucifera, Nov 2008 (3 ♀♀); F. Guarani, ex. C. nucifera, Jun 2016 (2 ♀♀, 2 DN, 2 PN); Limeira, ex. C. nucifera, Jun 2017 (2 ♀♀).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the redescription presented by Castro et al. (2019).

Tenuipalpus heveae Baker, 1945

Records in Bahia. Castro et al. 2013: 95; Castro et al. 2017: 421; Castro et al. 2018: 1578; present study.

Specimens examined. CEPLAC, ex. H. brasiliensis, Mar 2021 (1 ♂, 5 ♀♀, 1 LV).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the redescription presented by Castro et al. (2017).

Tenuipalpus odoratus Souza, Castro & Oliveira, 2019

Records in Bahia. Souza et al. 2019: 544. This species was not collected in the present study.

Tenuipalpus orchidofilo Moraes & Freire, 2001

Records in Bahia. Silva et al. 2022: 1. This species was not collected in the present study.

*Tenuipalpus pacificus Baker, 1945

Records in Bahia. present study

Specimens examined. Urban area (Ilhéus), ex. Phalaenopsis sp., Apr 2019 (8 ♂♂, 36 ♀♀, 12 DN, 12 PN, 20 LV).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the original description by Baker (1945) and to the redescriptions presented by Meyer (1993) and Beard et al. 2013.

Tenuipalpus panici De Leon, 1965

Records in Bahia. Nascimento et al. 2022: 2196.

*Tenuipalpus uvae De Leon, 1962

Records in Bahia. Present study.

Specimens examined. F. Bela Vista, ex. S. mombin, Apr 2007 (2 ♂♂, 2 ♀♀, 2 DN, 1 LV); F. Barra, ex. H. bihai, Aug 2007 (1 ♀); UESC, ex. S. mombin, Aug 2017 (1 ♂, 5 ♀♀, 1 DN).

Remarks. The morphology of the females collected in the present study is similar to the original description by De Leon (1962).

Key to the 16 tenuipalpid species reported from Bahia state territory

Based on adult females.

1. Opisthosoma with three setae in setal row C (c1, c2 and c3) (Figures 2A, B)

...... 2

— Opisthosoma with two setae in setal row C (c1 and c3) (Figure 2C)

...... 3

2. Opisthosoma with three setae in setal row D (d1, d2 and d3) (Figure 2A)

...... Raoiella : R. indica

— Opisthosoma with two setae in setal row D (d1 and d3) (Figure 2B)

...... Dolichotetranychus : D. floridanus

3. Opisthosoma with setae h2 long and whip-like, at least four times longer than other dorsal opisthosomal setae (Figures 2D, 3H)

...... Tenuipalpus 4

— Opisthosoma with setae h2 not whip-like, similar in form to other dorsal opisthosomal setae (Figures 4A, E, H)

...... Brevipalpus 10

4. Dorsal idiosoma with a pair of lateral projections anteriad of prodorsal seta sc2 and lateral to anterior opisthosomal seta c3 (Figure 2C)

...... T. coyacus

— Dorsal idiosoma without lateral projections anteriad of prodorsal seta sc2 and lateral to anterior opisthosomal seta c3 (Figure 2D)

...... 5

5. Coxisternal region with two pairs of setae 3a (3a1 and 3a2) (Figures 2D, E)

...... 6

— Coxisternal region with a single pair of setae 3a (Figures 3A, B, G, H)

...... 7

6. Coxisternal region with two pairs of setae 4a (4a1 and 4a2) (Figure 2D); genu III with one seta (Figure 2H)

...... T. pacificus

— Coxisternal region with a single pair of setae 4a (Figure 2F); genu III nude (Figure 2G)

...... T. orchidofilo

7. Femur IV with two setae (d and ev′) (Figures 3C, D)

...... T. panici

— Femur IV with one seta (ev′) (Figure 3E)

...... 8

8. Genua I and II with one seta each (d) (Figure 3F)

...... T. heveae

— Genua I and II with three setae each (d, l′ and l″) (Figures 3I, J)

...... 9

9. Tibia IV with three setae (d, v′ and v″) (Figure 3K)

...... T. uvae

— Tibia IV with two setae (v′ and v″) (Figure 3L)

...... T. odoratus

10. Opisthosoma with two setae in setal row F (f2 and f3) (Figures 4A, E)

...... 11

— Opisthosoma with one seta setal row F (f3) (Figures 4H, 5D)

...... 12

11. All dorsal setae (v2, sc1, sc2, c1, c3, d1, d3, e1, e3, f2, f3, h1 and h2) with similar size and shape (Figure 4A); tarsus II with two solenidia (Figure 4B); spermatheca vesicle rounded, with thick walls, a series of fine finger-like projections along the distal margin, and a bubble internally (Figure 4C)

...... B. californicus s.l.

— Dorsocentral setae flattened (c1, d1, e1 and h1) and much larger than dorsolateral seta (c3, d3, e3, f2, f3 and h2) (Figures 4E, G); tarsus II with one solenidion (Figure 4F); spermatheca vesicle oval, with fine walls, without distal projections, and no internal bubble (Figure 4D)

...... B. tuberellus

12. Tarsus II with one solenidion distally (Figure 4I)

...... B. obovatus

— Tarsus II with two solenidia distally (Figure 5B)

...... 13

13. Palp femorogenu with a narrow dorsal seta (Figure 5A); spermatheca vesicle oval, with a strong distal stipe (Figure 5C); cuticle on dorsal opisthosoma between setae e1-e1 to h1-h1 usually with strong chevrons (V-shaped folds), becoming much weaker towards h1-h1 (Figure 5D)

...... B. yothersi

— Palp femorogenu with a broad flat dorsal seta (Figure 5E); spermatheca vesicle rounded, without stipe, or spermatheca often not developed (Figures 5F, I, M); cuticle on dorsal opisthosoma between setae e1-e1 to h1-h1 without strong chevrons (Figure 5J)

...... 14

14. Genital plate with mostly transversely aligned elements, with ''warts'' or cell elements fused to form transverse bands (Figure 5G)

...... B. papayensis

— Genital plate not as above, with ''warts'' or cell elements fused to form large cells (Figure 5K)

...... 15

15. Opisthosoma with setae e3, f3, h1, h2 broad, 9–13 μm long (Figure 5J); spermatheca vesicle rounded (Figure 5I)

...... B. feresi

— Opisthosoma with setae e3, f3, h1, h2 moderately broad, 7–10 μm long (Figure 5N); spermatheca vesicle not visible, spermathecal duct ends in a membranous bulb (Figure 5M)

...... B. phoenicis s.s.

Discussion

With the 5 new species records of B. feresi, B. papayensis, T. coyacus, T. pacificus and T. uvae presented in the present study, the number of Tenuipalpidae species reported from Bahia state is raised to 16. The majority of published flat mite records in the checklist referred to B. phoenicis. As highlighted in the remarks for that species record, literature prior to Beard et al. (2015) should be considered to be B. phoenicis sensu lato until vouchers are examined to confirm the specific identification. On the other hand, females collected in the present study were able to be confirmed as B. phoenicis sensu stricto. Among the specimens collected in the present study, the most frequently identified species were (in descending order): B. yothersi, B. papayensis, B. feresi, R. indica and T. coyacus. The species Brevipalpus yothersi, B. papayensis and R. indica, together with D. floridanus, T. heveae, T. pacificus, B. phoenicis s.l., B. californicus and B. obovatus are all considered to be pests around the world (Hoy 2011; Vacante 2015; Beard et al. 2013, 2015, 2018; Kitajima 2020; Lillo et al. 2021).

The red palm mite, R. indica, is an important pest of bananas, coconut and other Arecaceae worldwide (Flechtmann and Etienne 2004; Hoy 2011; Kane et al. 2012; Vacante 2015), and has been reported causing damage to the açaí palm Euterpe oleracae in southern Bahia (Nuvoloni et al. 2021). Among the samples collected in the present study, damage to coconut Cocus nucifera and manilla palm Veitchia merrillii were also observed. Coconut leaves were observed with large numbers of chlorotic points, necrosis, dryness and even death of the basal leaves, while young leaves appeared completely browned on the ornamental palm V. merrillii due to the removal of cell contents by R. indica, and caused the plant to enter into premature senescence.

Although D. floridanus, an important pest of pineapple in several countries (Hoy 2011; Beard et al. 2013; Vacante 2015; Seeman et al. 2016), has been reported from pineapple in Bahia by Sanches and Flechtmann (1982) in association with leaf necrosis, samples collected in the present study did not show any obvious damage produced by the mite. Likewise, the flat mite T. heveae, an important pest of Hevea brasiliensis (see Pontier et al. 2000), was not observed to be causing significant damage in the present study, even though damage to some rubber tree clones has previously been reported in Bahia (Castro et al. 2013). On the other hand, severe damage by T. pacificus, a pest of orchids worldwide (Pritchard 1951; Krantz and Walter 2009), was observed on Phalaenopsis sp. in the present study, with leaves presenting a large number of chlorotic points. Damage to the orchid Dendrobium phalaenopsis were recently reported in the state of Bahia, and was probably caused by the flat mites T. orchidofilo, B. yothersi and B. californicus (see Silva et al. 2022).

There are known or implicated vectors of plant viruses among the Brevipalpus species reported in the present study. Brevipalpus yothersi is a vector of CiLV-C (Ramos-González et al. 2016) and PFGSV (Ramos-Gonzalez et al. 2020); B. papayensis is considered a vector of CiLV-C and CoRSV (Nunes et al. 2018); B. phoenicis s.l. is implicated in the possible transmission of Zoned chlorosis in citrus trees (Kitajima 2020); B. californicus is considered a vector of Orchid fleck virus (OFV) (Garcia-Escamilla et al. 2018; Beltran-Beltran et al. 2020; Fife et al. 2021); and finally B. obovatus is considered a vector of Solanum violifolium ringspot virus (SvRSV) (Ramos-Gonzalez et al. 2022).

The State of Bahia is located in the Northeast of Brazil and includes three natural Brazilian biomes, the ''Cerrado'', ''Caatinga'' and Atlantic Forest, each characterized by different physical and biological characteristics including soil, rain and vegetation (Santos et al. 2018). Although tenuipalpid mites were found in all three biomes in Bahia state territory, the number of records was much higher in the Atlantic Forest, with 61% of all reports from this biome, followed by the ''Caatinga'' (33%) and the ''Cerrado'' (6%). Based on that irregular distribution, the importance of more studies in the ''Cerrado'' and ''Caatinga'' biomes becomes clear, especially as these latter biomes have a warm climate that could be favorable to tenuipalpid species (Baker and Tuttle 1987; Laranjeira et al. 2015).

This study presents an overview of the tenuipalpid species reported from the Bahia state territory, expanding the known records and host plants for this family of mites. Given the importance of this family as phytophagous pests and disease vectors, further collections that include ornamentals, fruit, and commercial plantations, should be undertaken to understand the effect of environmental factors present in each biome on the frequency and abundance of tenuipalpid species, especially in the ''Cerrado'' and ''Caatinga''.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ''Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior'' (CAPES) for the fellowships to RSN (Finance Code 001), and RSM (PNPD/Agronomy Proc. 88882.305808/2018-1), the ''Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo'' (FAPESP) for the research grant to ADT (Proc. 2018/12252-8 and 2019/25078-9), and UESC, ESALQ, UNESP and USDA for the support. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA; USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

References

- Almeida D.O., Silva S.X.B., Chumbinho E.A., Laranjeira F.F., Ledo C.D.S. 2010. Incidência de ácaros Brevipalpus sp. em pomares e frutos do Recôncavo Baiano. In: Anais da Jornada Científica Embrapa Mandioca e Fruticultura. Cruz das Almas: EMBRAPA. pp. 2.

- Almeida E.M., Figueira A.R. 2014. Primeiro relato do Coffee ringspot virus (CoRSV) no Oeste da Bahia. Coffee Sci., 9(4): 558-561.

- Alves J.L.S., Ferragut F., Mendonça R.S., Tassi A.D., Navia D. 2019. A new species of Brevipalpus (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) from the Azores Islands, with remarks on the B. cuneatus species group. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 24(11): 2184-2208. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.24.11.10

- Arena G.D., Ramos-González P.L., Nunes M.A., Ribeiro-Alves M., Camargo L.E., Kitajima E.W., Freitas-Astúa J. 2016. Citrus leprosis virus C infection results in hypersensitive-like response, suppression of the JA/ET plant defense pathway and promotion of the colonization of its mite vector. Front. Plant Sci., 7(1757): 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01757

- Baker E.W. 1945. Mites of the genus Tenuipalpus (Acarina: Trichadenidae). Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash., 47(2): 33-38.

- Baker E.W. 1949. The genus Brevipalpus (Acarina: Pseudoleptidae). Am. Midl. Nat., 42(2): 350-402. https://doi.org/10.2307/2422013

- Baker E.W., Pritchard A.E. 1956. False spider mites of the genus Dolichotetranychus (Acarina: Tenuipalpidae). Hilgardia, 24(13): 357-381. https://doi.org/10.3733/hilg.v24n13p357

- Baker E.W., Tuttle D.M. 1987. The false spider mites of Mexico (Tenuipalpidae: Acari). U. S. Dep. of Agric. Res. Serv., Tech. Bull., 1706: 1-236.

- Banks N. 1904. A treatise on the Acarina or mites. Proc. U.S. Natl. Mus., 28: 1-114. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.28-1382.1

- Bastianel M., Novelli V.M., Kitajima E.W., Kubo K.S., Bassanezi R.B., Machado M.A., Freitas-Astúa J. 2010. Citrus Leprosis: Centennial of an unusual mite-virus pathosystem. Plant Dis., 94(3): 284-292. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-94-3-0284

- Beard J.J., Ochoa R., Bauchan G.R., Trice M.D., Redford A.J., Walters T.W., Mitter C. 2013. Flat mites of the world edition 2. Identification Technology Program, CPHST, PPQ, APHIS, USDA. [15 September 2022]. Available from: http://idtools.org/id/mites/flatmites.

- Beard J.J., Ochoa R., Braswell W.E., Bauchan G.R. 2015. Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes) species complex (Acari:Tenuipalpidae) - a closer look. Zootaxa, 3944(1): 1-67. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3944.1.1

- Beard J.J., Ochoa R., Bauchan G.R., Pooley C., Dowling A.P. 2018. Raoiella of the world (Trombidiformes: Tetranychoidea: Tenuipalpidae). Zootaxa, 4501(1): 1-301. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4501.1.1

- Beltran-Beltran A.K., Santillán-Galicia M.T., Guzmán-Franco A.W., Teliz-Ortiz D., Gutiérrez-Espinoza M.A., Romero-Rosales F., Robles-García P.L. 2020. Incidence of Citrus leprosis virus C and Orchid fleck dichorhavirus Citrus Strain in Mites of the Genus Brevipalpus in Mexico. J. Econ. Entomol., 113(3): 1576-1581. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa007

- Bondar G. 1928. Relatórios anuais de 1921 a 1927. Boletim do Laboratório de Patologia Vegetal, 4: 39-46.

- Câmara I.G. 2003. Brief history of conservation in the Atlantic Forest. In: Galindo-Leal C., Câmara I.G. (Eds). The Atlantic Forest of South America: biodiversity status, threats, and outlook. Washington, USA: Island Press, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science at Conservation International. pp. 31-42.

- Castro E.B., Nuvoloni F.M., Mattos C.R.R., Feres R.J.F. 2013. Population fluctuation and damage caused by phytophagous mites on three rubber tree clones. Neotrop. Entomol., 42: 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-012-0088-y

- Castro E.B., Ramos F.A.M., Feres R.J.F., Ochoa R., Bauchan G.R. 2017. Redescription of Tenuipalpus heveae Baker (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and description of a new species from rubber trees in Brazil. Acarologia, 57(2): 421-458. https://doi.org/10.1051/acarologia/20174166

- Castro E.B., Nuvoloni F.M., Feres R.J.F. 2018. Population dynamics of the main phytophagous mites associated with rubber tree plantations in the state of Bahia, Brazil. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 23(8): 1578-1591. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.23.8.8

- Castro E.B., Tassi A.D., Barroso G., Feres R.J.F., Ochoa R. 2019. Redescription of Tenuipalpus coyacus De Leon (Trombidiformes: Tenuipalpidae), with a discussion on the ontogeny of leg setae. Intern. J. Acarol., 45(5): 280-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2019.1621932

- Castro E.B., Mesa N.C., Feres R.J.F., Moraes G.J.de., Ochoa R., Beard J.J., Demite P.R. 2022a. Tenuipalpidae Database. [20 July 2022]. Available from: http://www.tenuipalpidae.ibilce.unesp.br

- Castro E.B., Feres R.J.F., Mesa N.C., Moraes G.J.de. 2022b. A new flat mite of the genus Tenuipalpus Donnadieu (Trombidiformes: Tenuipalpidae) from Brazil. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 27(2): 368-380. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.27.2.10

- Cavalcante A.C.C., Noronha A.C.S., Barbosa C.J., Bragança A.D. 2006. Espécies de Brevipalpus (Acari, Tenuipalpidae) em maracujazeiro no município de Rio Real - BA. In: Anais da Semana de Ciências Agrárias, Ambientais e Biológicas. Cruz das Almas: UFRB. pp. 1.

- Childers C.C., French J.V., Rodrigues J.C.V. 2003. Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, B. phoenicis and B. lewisi (Acari: Tenuipalpidae): a review of their biology, feeding injury and economic importance. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 30: 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:APPA.0000006543.34042.b4

- Costa R.C.da, Araújo F.S.de., Lima-Verde L.W. 2007. Flora and life-form spectrum of deciduous thorn woodland (caatinga) in northeastern, Brazil. J. Arid Environ., 68(2): 237-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.06.003

- De Leon D. 1960. The genus Brevipalpus in Mexico, Part I (Acarina: Tenuipalpidae). Fla. Entomol., 43(4): 175-187. https://doi.org/10.2307/3492784

- De Leon D. 1962. Two new false spider mites from Mexico and a new distribution Record. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash., 64(3): 203-205.

- Fiaboe K.K.M., Gondim M.G.C.J., Moraes G.J.de., Ogol C.K.P.O., Knapp M. 2007. Surveys for natural enemies of the tomato red spider mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) in Northeastern and Southeastern Brazil. Zootaxa, 22(1395): 33-58. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1395.1.2

- Fife A., Carrillo D., Knox G., Iriarte F., Dey K., Roy A., Ochoa R., Bauchan G., Paret M., Martini X. 2021. Brevipalpus-transmitted Orchid Fleck Virus Infecting Three New Ornamental Hosts in Florida. J. Integr. Pest Manag., 12(1): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmab035

- Flechtmann C.H.W., Abreu J.M. 1973. Ácaros fitófagos do Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Cien. Cult., 25(3): 244-251.

- Flechtmann C.H.W. 1976. Preliminary report on the false spider mites (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) from Brazil and Paraguay. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash., 78(1): 58-64.

- Flechtmann C.H.W., Arleu R.J. 1984. Oligonychus coffeae (Nietner, 1861), um ácaro tetraniquídeo da seringueira (Hevea brasiliensis) novo para o Brasil e observações sobre outros ácaros desta planta. Ecossistema, 9: 123-125.

- Flechtmann C.H.W., Etienne J. 2004. The red palm mite, Raoiella indica Hirst, a threat to palms in the Americas (Acari: Prostigmata: Tenuipalpidae). Syst. Appl. Acarol., 9: 109-110. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.9.1.16

- Garcia-Escamilla P., Duran-Trujillo Y., Otero-Colina G., Valdovinos-Ponce G., Santillán-Galicia M.T., Ortiz-Garcia C.F., Velazquez-Monreal J.J., Sanchez-Soto S. 2018. Transmission of viruses associated with cytoplasmic and nuclear leprosis symptoms by Brevipalpus yothersi and B. californicus. Trop. Plant Pathol., 43: 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-017-0195-8

- Gerson U. 2008. The Tenuipalpidae: an under-explored family of plant-feeding mites. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 13(2): 83-101. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.13.2.1

- Hoy M.A. 2011. Agricultural acarology: introduction to integrated mite management. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press. pp. 410.

- Kane E.C., Ochoa R., Mathurin G., Erbe E.F., Beard J.J. 2012. Raoiella indica Hirst (Acari: Tenuipalpidae): an exploding mite pest in the neotropics. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 57(3): 215-225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9541-1

- Kitajima E.W. 2020. An annotated list of plant viruses and viroids described in Brazil (1926-2018). Biota Neotrop., 20(2): 1-101. https://doi.org/10.1590/1676-0611-bn-2019-0932

- Krantz G.W., Walter D.E. 2009. A Manual of Acarology - 3rd ed. Lubbock, Texas, USA: Texas Tech University. pp. 807.

- Laranjeira F.F., Silva S.X.B., Andrade E.C., Almeida D.O., Kitajima E.W., Navia D., Freitas-Astúa J. 2011. Mapeamento e caracterização de viroses associadas a Brevipalpus sp. na Bahia. Cruz das Almas: Boletim de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento da Embrapa Mandioca e Fruticultura. pp. 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-015-9921-4

- Laranjeira F.F., de Brito Silva S.X., de Andrade E.C., Almeida D.O., da Silva T.S.M., Soares A.C.F., Freitas-Astúa J. 2015. Infestation dynamics of Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes) (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) in citrus orchards as affected by edaphic and climatic variables. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 66(4): 491-508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-015-9921-4

- Lillo E.de., Freitas-Astúa J., Kitajima E.W., Ramos-González P.L., Simoni S., Tassi A.D., Valenzano D. 2021. Phytophagous mites transmitting plant viruses. Entomol. Gen., 41(5): 439-462. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2021/1283

- Melo J.W.S., Navia D., Mendes J.A., Filgueiras R.M.C., Teodoro A.V., Ferreira J.M.S., Guzzo E.C., Souza I.V., Mendonça R.S., Calvet E.C., Neto A.A.P., Gondim Jr M.G.C., Morais E.G.F., Godoy M.S., Santos J.R., Silva R.I.R., Silva V.B., Norte R.F., Oliva A.B., Santos R.D.P., Domingos C.A. 2018. The invasive red palm mite, Raoiella indica Hirst (Acari: Tenuipalpidae), in Brazil: range extension and arrival into the most threatened area, the Northeast Region. Internat. J. Acarol., 44(4): 146-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2018.1474945

- Mesa N.C., Ochoa R., Welbourn W.C., Evans G.A., Moraes G.J.de. 2009. A catalog of the Tenuipalpidae (Acari) of the world with a key to genera. Zootaxa, 2098: 1-185. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2098.1.1

- Meyer M.K.P. 1993. A revision of the genus Tenuipalpus Donnadieu (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) in the Afrotropical region. Entomol. Mem. of the Dep. of Agric. Repub. S. Afr., 88: 1-84.

- Mineiro J.L.C., Sato M.E., Ochoa R., Beard J., Bauchan G. 2018. Revisão taxonômica do ácaro da leprose dos citros e sua distribuição no Brasil. Citrus Res. Technol., 39(1036): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4322/crt.17147

- Moraes G.J.de., Flechtmann C.H.W. 1981. Ácaros fitófagos do Nordeste do Brasil. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras., 16(2): 177-186.

- Moraes G.J.de., Flechtmann C.H.W. 2008. Manual de Acarologia: Acarologia Básica e Ácaros de Plantas Cultivadas no Brasil. Ribeirão Preto: Holos. pp 288.

- Moraes G.J.de., Freire R.A.P. 2001. A new species of Tenuipalpidae (Acari: Prostigmata) on orchid from Brazil. Zootaxa, 1: 1-10.

- Nascimento R.S., Castro E.B., Tassi A.D., Ochoa R., Oliveira A.R. 2022. First record of Tenuipalpus panici De Leon (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) in South America, with new morphological data and a discussion on the ontogeny of setae. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 27(11): 2195-2211. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.27.11.6

- Navia D., Mendonça R.S., Ferragut F., Miranda L.C., Trincado R.C., Michaux J., Navajas M. 2013. Cryptic diversity in Brevipalpus mites (Tenuipalpidae). Zool. Scr., 42(4): 406-426. https://doi.org/10.1111/zsc.12013

- Noronha A.C.S., Carvalho J.D., Caldas R.C. 1997. Ácaros em citros nas condições de Tabuleiros Costeiros. Rev. Bras. Frutic., 19(3): 373-376.

- Noronha A.C.S., Cavalcante A.C.C. 2011. Aspectos biológicos de Brevipalpus obovatus Donnadieu (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) em maracujazeiro. Arq. Inst. Biol., São Paulo, 78(3): 453-457. https://doi.org/10.1590/1808-1657v78p4532011

- Nunes M.A., Mineiro J.L.C.de., Rogero L.A., Ferreira L.M., Tassi A.D., Novelli V.M., Kitajima E.W., Freitas-Astúa J. 2018. First report of Brevipalpus papayensis Baker (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) as vector of Coffee ringspot virus and Citrus leprosis virus C. Plant Dis., 102: 1046. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-07-17-1000-PDN

- Nuvoloni F.M., Andrade L.M.S., Castro E.B., Rezende J.M., Araújo M.S. 2021. First report of damage and population dynamics of Raoiella indica Hirst (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) on Euterpe oleracea (Arecaceae) in the State of Bahia, Brazil. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 26(9): 1769-1775. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.26.9.10

- Nuvoloni F.M., Pinto J.A., Andrade L.M.S. 2022. Ácaros predadores associados a um sistema agroflorestal de açaí (E. oleracea, Arecaeae) e cupuaçu [Theobroma grandiflorum (Willd. Ex Spreng), Malvaceae] no sul do estado da Bahia. Entomol. Commun., 4. https://doi.org/10.37486/2675-1305.ec04011

- Oliveira V.D.S., Noronha A.D.S., Argolo P.S., Carvalho J.D. 2007. Acarofauna em pomares cítricos nos municípios de Inhambupe e Rio Real no Estado da Bahia. Magistra, 19(3): 257-261.

- Pontier K.J.B., Moraes G.J.de., Kreiter S. 2000 Biology of Tenuipalpus heveae (Acari, Tenuipalpidae) on rubber tree leaves. Acarologia, 41: 423-427.

- Pritchard A.E. 1951. Control of orchid mites: false spider mites and spider mites must be distinguished for proper control purposes. Calif. Agric., 5(9): 11.

- Ramalho T.O., Figueira A.R., Sotero A.J., Wang R., Geraldino-Duarte P.S., Farman M., Goodin M.M. 2014. Characterization of Coffee ringspot virus-Lavras: A model for an emerging threat to coffee production and quality. Virology, 464(465): 385-396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.031

- Ramos-González P.L., Chabi-Jesus C., Guerra-Peraza O., Breton M., Arena G., Nunes M., Freitas-Astúa J. 2016. Phylogenetic and molecular variability studies reveal a new genetic clade of Citrus leprosis virus C. Viruses, 8(6): 1-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/v8060153

- Ramos-González P.L., Santos G.F., Chabi-Jesus C., Harakava R., Kitajima E.W., Freitas-Astúa J. 2020. Passion fruit green spot virus genome harbors a new orphan ORF and highlights the flexibility of the 5′-end of the RNA2 segment across cileviruses. Front. Microbiol., 11(206): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00206

- Ramos-González P.L., Chabi-Jesus C., Tassi A.D., Calegario R.F., Harakava R., Nome C.F., Kitajima E.W., Freitas-Astua J. 2022. A Novel Lineage of Cile-Like Viruses Discloses the Phylogenetic Continuum Across the Family Kitaviridae. Front. Microbiol., 13: 1-22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.836076

- Ratter J.A., Ribeiro J.F., Bridgewater S. 1997. The Brazilian Cerrado Vegetation and Threats to its Biodiversity. Ann. Bot., 80(3): 223-230. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1997.0469

- Ribeiro A.E.L., Boaretto M.A.C., Viana A.E.S., Oliveira E., Lima M.S.D., Khouri C.R., Rocha S.A.A. 2001. Ocorrência do ácaro Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes, 1939) (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) no polo cafeeiro do planalto de Vitória da Conquista, BA. In: Simpósio de Pesquisa dos Cafés do Brasil. Vitória: SBICafé Biblioteca do Café. p. 2022-2030.

- Sampaio E.V.S.B. 1995. Overview of the Brazilian Caatinga. In: Bullock S.H., Mooney H.A., Medina E. (Eds). Seasonally tropical dry forests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35-63. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511753398.003

- Sanches N.F., Flechtmann C.H.W. 1982. Acarofauna do abacaxizeiro na Bahia. An. Soc. Entomol. Bras., 11: 147-155. https://doi.org/10.37486/0301-8059.v11i1.272

- Santos Filho H.P., Lima A.A., Barbosa C.J., Borges A.L., Noronha A.C.S., Santos C.C.F., Caldas R.C., Chagas C.M., Myay T. 1999. Definhamento precoce do maracujazeiro. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, Embrapa Mandioca e Fruticultura, Comunicado Técnico, 60: 1-5.

- Santos L.A., Carvalho Júnior O.A., Guimarães R.F., Gomes R.A.T. 2018. Áreas prioritárias para regularização fundiária no estado da Bahia (Brasil). Finisterra, 53(107): 27-50. https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis10618

- Seeman, O.D., Loch, D.S., McMaugh, P.E. 2016. Redescription of Dolichotetranychus australianus (Trombidiformes: Tenuipalpidae), a pest of bermuda grass Cynodon dactylon (Poaceae). Internat. J. of Acarol. 42(4): 193-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2016.1153143

- Silva A.C.S., Carvalho C.A.L., Machado C.S., Silva E.S., Silva L.F.A., Alves R.M.O., Sodré G.S. 2022. Tenuipalpus Donnadieu, 1875 and Brevipalpus Donnadieu, 1775 in cultivation of orchid Dendrobium phalaenopsis Fitzg. Cienc. Rural, 52(11): 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20210368

- Silva S.X.B., Laranjeira F.F., Andrade E.C., Almeida D.O. 2012a. Dinâmica da infestação de Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes, 1939) (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) em pomares cıtricos da Bahia, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Frutic., 34(1): 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-29452012000100012

- Silva S.X.B., Laranjeira F.F., Andrade E.C., Soares A.C.F., Almeida D.D.O. 2012b. Minimum sample size, prevalence and incidence of Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes) (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) in Recôncavo Baiano. Magistra, 24: 17-25.

- Souza K.S., Castro E.B., Tassi A.D., Navia D., Oliveira A.R. 2019. A new species of Tenuipalpus Donnadieu (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) from Cedrela odorata L. (Meliaceae), from Bahia, Brazil, with ontogeny of chaetotaxy. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 24(4): 544-559. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.24.4.2

- Vacante V. 2015. The Handbook of Mites of Economic Plants: Identification, Bio-ecology and Control. Boston, USA: Cabi. pp. 890. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845939946.0001

- Welbourn W.C., Ochoa R., Kane E.C., Erbe E.F. 2003. Morphological observations on Brevipalpus phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) including comparisons with B. californicus and B. obovatus. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 30: 107-133. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:APPA.0000006545.40017.a0

2023-01-24

Date accepted:

2023-04-19

Date published:

2023-05-24

Edited by:

Akashi Hernandes, Fabio

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2023 Nascimento, Renata S.; Souza, Kaélem S.; Melo, Elisangela A. S. F. ; Tassi, Aline D.; Castro, Elizeu B. ; Navia, Denise; de Mendonça, Renata S. ; Ochoa, Ronald and Oliveira, Anibal R.

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)